Sussex

BRIGHTON and HOVE

In the eighteenth century, the little fishing village of Brighthelmstone grew into a fashionable watering place, reaching its zenith when the Prince Regent commissioned his exotically extravagant onion-domed palace, the Royal Pavilion.

In 1761, the Countess of Huntingdon, always eager to bring the gospel to her aristocratic circle, ordered the building of a chapel in North Street. This was later replaced by a larger church, but neither building survives.

In the nineteenth century, much of the evangelical activity in the town centred on the Elliott family of Westfield Lodge. The best known member was the hymn writer Charlotte Elliot (1789-1871). She was one of several daughters of Charles Elliott and his wife Eling, daughter of Henry Venn of Huddersfield, a friend and supporter of John Wesley. The Elliotts were associated with the new parish church of St Mary's in Upper Rock Gardens and were instrumental in the foundation of St Mary's Hall School in Eastern Road.

Charlotte Elliott's grave

The Elliott family vault is in the churchyard of St Andrew's Old Church in Church Road, Hove (BN3 2DB). As well as the parents, the names at least five daughters and two sons are inscribed here. They include Rev Henry Venn Elliott, incumbent of St Mary's Church and Rev Edward Bishop Elliott, for 22 years vicar of St Mark's, Brighton.

The inscription to Charlotte Elliott mentions her best known hymn. She spent much of her life as an invalid and was frequently unable to take a full part in the activities of her siblings. On one particular occasion, she was prevented by illness from helping with a sale of work organized by her brother. Frustrated and disappointed, she stayed at home and penned the famous lines of Just as I am, summarizing the Christian experience of obedience and submission to the will of God.

One who knew much about obedience and submission was James Hudson Taylor (1832-1904), who had a life-changing experience in Brighton on June 25th 1865. Having already spent several years in China as a pioneer missionary, he had returned home to complete his medical studies and consider his future ministry. Visiting friends in the town, he attended a Sunday morning service, probably in the Dome, now a large complex near the Pavilion used as a theatre, museum and art gallery. Unable to bear the sight of rows of well-to-do, hymn-singing Christians, while millions in China had no chance to hear the gospel, he walked out and wandered onto the beach, deep in thought and prayer. The outcome was the foundation of the China Inland Mission, which in due course sent out hundreds of eager missionaries to fulfil his vision of taking the gospel to every province of China.

On the corner of Holmes Avenue and Nevill Avenue in Hove is Bishop Hannington Memorial Church, built in 1938. It commemorates another pioneer missionary, James Hannington Bishop of East Equatorial Africa, who met a violent death in Uganda in 1885.

HURSTPIERPOINT

On the road from Hassocks, a large white-painted house on the right is known as St George's House (actually 9 Hassocks Road BN6 9QP). Now apparently divided into several flats and maisonettes, this was the home of Charles Hannington, a wealthy businessman, whose son James Hannington was born here in 1847. After falling out with the rector of Holy Trinity, Charles Hannington built St George's church behind his house, and James, after studying at Oxford, was ordained and spent seven years as curate-in-charge.

In 1882, James Hannington was accepted for service with the Church Missionary Society and was sent to East Africa. Setting out from Zanzibar, he reached Lake Victoria, but had to return to England through ill-health in 1883. Gaining rapid promotion, he was consecrated Bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa in 1884, and within a few months set out again with a large expedition to find a shorter route to Lake Victoria. The King of Uganda, however, suspected that the enterprise had military motives and Hannington was captured on 21st October 1885 and murdered eight days later.

At Holy Trinity church, the rift with Hannington's father was presumably forgotten as there is an impressive memorial brass of the bishop, described as evangelist and martyr, with a lifelike portrait set into a slab of marble. It faces the small entrance on the north east side of the church.

LEWES

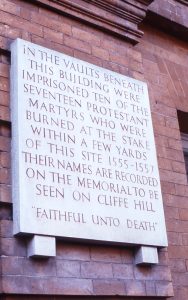

Martyrs' Memorial, Lewes

This ancient Sussex town celebrates Guy Fawkes night with rather more vigour and enthusiasm than most other places. The reason is that no fewer than seventeen Protestants were burned at the stake here in Queen Mary's reign, and hence the failure of the Catholic plot to blow up parliament in 1605 has always had a special significance.

In the centre of the town, the High Street starts at the pedestrianised section by Cliffe Bridge and then runs steeply uphill towards the castle. At the crest of the hill, close to the war memorial, is the Town Hall (BN7 2QS). Here a Victorian brick facade covers much older parts of the building which until 1893 was the Star Inn. A star is incorporated into the wrought iron lamp bracket over the front entrance.

The martyrdoms took place in front of the Star Inn. On 22nd June 1557, ten men and women suffered together, including Richard Woodman whose story is told below. A plaque records that this group was held in the medieval vaults beneath the Town Hall, whose steps may still be seen. The main memorial to the martyrs is a granite obelisk on Cliffe Hill, which can be seen from the High Street looking across the valley of the Ouse. More energetic visitors may wish to climb up to the monument, which gives a good view of the town and is the focus of the firework celebrations. The names and home towns of each martyr are inscribed at the base.

In Malling Street across Cliffe Bridge is Jireh Chapel (BN7 2RD), built in 1805 and recently restored. It was built for William Huntington (1745-1813), an eccentric coalheaver whose life was colourful, to say the least. Following his conversion, he awarded himself the title of S.S., standing for sinner saved, which he always appended to his name. He began a long preaching career, building himself a chapel in London, and adopting strongly Calvinistic views. Those who criticized his teaching or methods were damned as knaves or fools. Huntington was buried here and his tombstone has been put together with those of other former ministers on a raised platform behind the church. The inscription is almost illegible, but has an interesting self-composed epitaph beginning Here lies the coalheaver who departed his life July 1st 1813 in the 69th year of his age, beloved of his God but abhorred of men....

WARBLETON

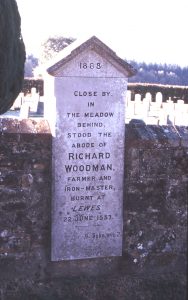

Richard Woodman memorial

Set among narrow lanes a few miles from Heathfield, the village lies on the southern slope of the Sussex weald. In Tudor times this was a centre of the iron-working industry, wood from surrounding forests providing an ample supply of fuel.

Richard Woodman (1524-1557), a leading local ironmaster and farmer, employed a hundred men and was churchwarden of St Mary's Church (TN21 9BD). He was also a Protestant, believing in salvation by faith, and rebuked the local vicar when he taught otherwise. He was arrested and imprisoned for eighteen months, but on his release continued to travel and preach, at one time taking refuge in France for a few weeks. Woodman left a detailed description of the events surrounding his trial which is faithfully recorded in Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

After a dramatic arrest at his house in Warbleton, Woodman was taken to London and underwent numerous examinations, during which his knowledge of scripture proved a match for the leading theologians of the day. He was finally condemned at a hearing in the present Southwark Cathedral, taken to Lewes and burned at the stake with nine others on 22nd June 1557.

Woodman's house stood next to the church and his meadow is now used as an extension to the graveyard. A memorial is set into the south churchyard wall, not far from the step he would use to reach the church. In the second storey of the church tower there is a small room with an ancient ironclad door and an elaborate lock, which may have been used as a prison and Woodman is said to have been confined here. On the north wall of the church is a print showing the martyrdom scene at Lewes.

WINCHELSEA

Wesley's tree

Like its neighbour Rye, Winchelsea is a town set on a hill. At its centre, the splendid church of St Thomas is rich in medieval tombs and was once much larger. On the grass verge by the churchyard a small plaque marks the spot where John Wesley, at the age of eighty-seven, preached his last open-air sermon on 7th October 1790. Almost the whole town turned out to hear him as he stood under an ash tree and urged them to Repent and believe the gospel. A new tree grows in place of the original, standing opposite the New Inn in German Street (TN36 4EN).

There is a Methodist Chapel of 1785 on the west side of the town. A plaque records that Wesley preached here in 1789 and again in 1790.

COOLHAM

The Blue Idol

On the A272 between Coolham and Coneyhurst, a turning to the south called Old House Lane leads to the curiously named Blue Idol, actually a Quaker Meeting House and guest centre (RH14 9DJ). The building is an ancient farmhouse, with half-timbering, white painted weatherboards and quarried roof tiles. It was acquired by William Penn (1644-1718) for the Society of Friends and he worshipped here while living at Warminghurst Place a few miles away. As with other Quaker centres, the beautiful orchard-like garden served as a burial ground and Penn's daughter Letitia lies here in an unmarked grave. In front of the main house is an old timber-framed barn, with an exhibition devoted to Penn's life and work.

WARMINGHURST

The place is almost impossible to find and appears to consist of the church, an adjacent farmhouse and little else. We reach it from the village of Ashington, which has itself been bypassed by the busy A24. William Penn lived at Warminghurst Place from 1677 to 1702, although his affairs took him away for long periods, including two visits to America. It was here that his ideas for the constitution of Pennsylvania took shape. Penn's friendship with the Stuart monarchs and many in the highest positions in the land did not protect him from the severity of the laws against non-conformist meetings. In 1684, he was charged at Arundel Quarter Sessions with being a factious and seditious person who doth frequently entertaine and keepe unlawfull Assemblyes and Conventicles in his dwelling house at Worminghurst....

In later life, Penn suffered financial problems and his last years were embittered by disputes over the future of Pennsylvania and by the misbehaviour of his son. Around 1707 he sold Warminghurst Place to the Anglican James Butler, who promptly demolished it so as not to leave a trace of the old Quaker. The church, no longer in regular use, has interesting box pews and an elaborate memorial to Butler, but no mention of Penn. Warminghurst Place stood across the fields to the south of the church.

GRAFFHAM

Nestling in the shelter of the South Downs, this peaceful village was the scene of a bitter family dispute, which mirrored the deep divisions in the Church of England in Victorian times. The whole episode reads like a novel by Trollope, but about the only visible clue to the story is found in the list of former vicars of St Giles' Church (GU28 0NJ). From 1805 to 1833 the rector was John Sargent, followed by Henry Edward Manning until 1851. The present church building dates from the 1870s, by which time most of the participants in the drama were dead or departed from the scene.

The story begins with John Sargent (1780-1833), who was born at Lavington Park. Educated at Eton and King's College, Cambridge, he came under the influence of Charles Simeon and was ordained in 1805. A committed evangelical, Sargent became rector of Graffham, together with the neighbouring parish of Woolavington. He served as an exemplary country parson and squire, bringing up a family of several daughters. One of his friends at Cambridge had been Henry Martyn (1781-1812), the pioneer missionary to India and Persia. Weak and exhausted, Martyn was returning to England when he died of consumption at Tokat in Turkey. The task of editing his diaries fell to Sargent, who thus introduced the Christian public to Martyn's extraordinary achievements.

Apart from this, Sargent's career was little different from any other incumbent of a country parish. It was among Sargent's daughters and their families that the ties of kinship and affection were torn apart by the religious controversies of the day. Caroline Sargent married Henry Manning, who became vicar of the parish on Sargent's death in 1833. Following her early death, Manning converted to Roman Catholicism in 1851 and eventually became a cardinal. Mary and Emily married, respectively, Henry and Samuel Wilberforce (1805-1873), sons of William Wilberforce. The marriage of Emily and Samuel was conducted by Sargent's old friend Charles Simeon. Finally, Sophia married George Dudley Ryder, son of the evangelical Bishop Henry Ryder.

The Oxford Movement, advocating a more sacramental liturgy for the Church of England and stressing historic continuity with Rome, began in the 1830s. It was promoted by John Henry Newman and Edward Pusey, and opposed with equal vigour by evangelicals. The movement split the families of Sargent's daughters, with Manning, Ryder and Henry Wilberforce eventually leaving the Church of England for Rome. Samuel Wilberforce alone remained within the Anglican fold, becoming Bishop of Oxford and later Bishop of Winchester. Through his wife Emily, he inherited Lavington Park and made the place his home. He died in 1873 following a fall from his horse and is buried at Woolavington. A marble plaque in the bell tower of St Giles commemorates Wilberforce and records that the church was rebuilt in his memory.

SELSEY

St Wilfrid's Chapel

Around the year 667, the energetic St Wilfrid of York (c630-709), was returning from France following his consecration as Bishop of Lindisfarne when he was shipwrecked on the Sussex coast near here. He narrowly avoided being killed by the local tribes who were still largely pagan.

Some fifteen years later, Wilfrid was in dispute with King Ecgfrith of Northumbria and in 681 sought refuge in Sussex, where he was favourably received by King Ethelwald. He stayed for five years and set to work to evangelise the South Saxons, gaining their confidence by teaching them to fish with nets. He founded a new bishopric at Selsey, which only transferred to Chichester in 1075 following the Norman Conquest.

One tradition holds that Wilfrid's original cathedral and monastery lie beneath the sea, but it seems more likely that they stood near the site of St Wilfrid's Chapel at Church Norton on the south side of Pagham harbour (PO20 9DT). The tiny chapel is all that remains if a much larger Norman church and stands within a deep defensive moat which surrounded the settlement. In the 1860s, the nave of the church was demolished and the materials, including a beautiful Norman font, used in the present St Peter's church at Selsey. Only the chancel of the original church was left, which formed the present chapel when the west wall was filled in with brickwork. It has four lancet windows with modern stained glass, one of which depicts scenes from the life of Wilfrid.