Central London

WESTMINSTER ABBEY

If Canterbury Cathedral is the spiritual heart of the Church of England, Westminster Abbey is the focus of the nation's collective grief and rejoicing. Royal weddings and funerals, great state occasions and the coronation of kings and queens have been celebrated here for nearly a thousand years.

The first abbey was founded by Edward the Confessor in 1065, and William the Conqueror stamped authority on his new kingdom by his coronation here on Christmas Day 1066, a few weeks after the Battle of Hastings. Most of the present abbey was built in the reign of Henry III between 1220 and 1272. Additions and improvements were added in subsequent centuries and the familiar West Towers were not completed until 1745.

Westminster Abbey

The days when a quiet afternoon could be spent strolling unhindered through the abbey precincts are long gone. The abbey is now an essential item on the tourist itinerary, so we have to join the queue at the North Transept - often long - and be herded around a fixed route, although greater space in the cloisters and nave give some opportunity to pause and reflect. The best plan is to buy a guidebook at the bookshop by the West Door to have something to read while waiting.

The great and the famous of past centuries are all interred here. Monarchs including Edward III victor of Crecy, Henry VII victor of Bosworth Field, and Elizabeth I victor of the Armada - as well as the less fortunate Mary Queen of Scots - have their elaborate canopied tombs. Dickens and Chaucer, Newton and Darwin, Handel and Purcell - their mortal remains are beneath our feet and often we are walking over them unawares. The scope of this guide is limited to those who influenced the spiritual life of the nation, so for full details the standard guidebooks should be consulted. In the north transept where we enter, for example, are statues of several nineteenth century statesmen - Peel and Palmerston, Disraeli and Gladstone - but also memorials those who saw slavery as an offence to the conscience of the nation. A few paces from the ticket office, and we are standing - probably unaware - on the tomb of William Wilberforce. A stone slab on the floor carries his name and dates. Just to the right against a pillar is a statue of Thomas Fowell Buxton his friend and successor in the fight against slavery.

The Abbey has relatively little stained glass, much of it lost to wartime bombing. What remains is mostly modern. Immediately above the right hand entrance, before we even reach the ticket office, is a window commemorating John Bunyan, with panels showing scenes from Pilgrim's Progress.

Our route takes us to the left through the North Ambulatory and thence up the steps to the chapel of Henry VII, forming the eastern part of the abbey. Here Queen Elizabeth I lies alongside her half-sister Queen Mary. Divided in life by religion and the marital complications of their father, Henry VIII, they are united in death. A modern inscription invites us to remember before God all those, who, divided at the Reformation by different convictions, laid down their lives for Christ and conscience sake. Further doctrinal explanations are tactfully avoided!

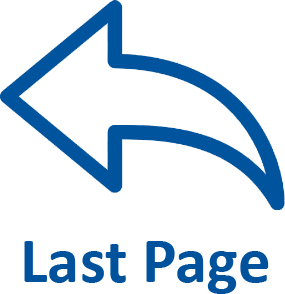

Shrine of Edward the Confessor

At the extreme east end is a chapel restored as memorial to the R.A.F after bomb damage in World War II. An inscription in the floor records this as the burial place of Oliver Cromwell's mortal remains from 1658 to 1661. The gruesome details of their subsequent history are also carefully avoided - and probably just as well! At the Restoration in 1660, Charles II sought vengeance on his father's executioners. The body of Cromwell was exhumed and hanged at Tyburn and his head impaled on Westminster Hall for twenty-four years. In the twentieth century, his skull finally came to rest in the chapel of his former college, Sidney Sussex, Cambridge.

We continue round by the south side, which brings us to the South Transept, famous as Poets Corner. Geoffrey Chaucer was buried here in 1400, but this was more connected with his position as Clerk of the Works to the Palace of Westminster than as author of The Canterbury Tales, the first great work in the English language. In recent times the definition of poet has been widened to include playwrights, actors and even broadcasters, and names continue to be added, despite the ever-decreasing wall space! Those relevant to our theme include John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, whose bust by Rysbrack on the south wall was placed here in the reign of George II. Seemingly out of place is a memorial to Granville Sharp, not a poet, but another hero in the battle against slavery. Sharp established the legal ruling that slavery could not exist in England and that a slave transported here was free the moment of arrival in Britain. A recent granite slab in the floor nearby celebrates Caedmon, the first English Christian poet who flourished around 670.

Poets Corner

On the west wall of the South Transept, some ten feet up, is Roubiliac's statue of Georg Handel, whose Zadok the Priest has been sung here at all coronations since it was composed for that of George II. The great composer, best known for his magnificent oratorio The Messiah, is buried beneath a stone slab on the floor. Nearby is a bust of John Keble, Victorian poet and hymnwriter.

Poets Corner has spilled out of the South Transept into the south aisle of the Nave. This part is normally roped off as visitors are diverted into the cloisters, but across the barrier we can see a joint medallion portrait of John and Charles Wesley. Originally it was just Charles who was to be honoured as a hymnwriter, but John was included at the suggestion of the nineteenth century Dean Stanley. Also here is a bust of Isaac Watts who rivals Charles as the greatest hymnwriter in the English language.

After a circuit of the Cloisters and optional visits to the Museum and Chapter House, we return to the Nave through the south door. Here is one of the best known tombs of all, that of David Livingstone, the Victorian missionary explorer. It lies just a few paces from the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, but unaccountably the official abbey guidebook fails to mention it at all. Livingstone, despite failing health, refused to leave Africa and died in 1873 at Chitambo, in present-day Zambia. His faithful African servants Susi and Chuma buried his heart at the spot, but embalmed his body and carried it to the coast and then brought it by sea to Southampton. It was laid to rest with much ceremony in the presence of Livingstone's long-lived father-in-law, the pioneer missionary Robert Moffatt. The inscription is taken from John 10, 16 Other sheep I have which are not of this fold: them also must I bring and they shall hear my voice.

The statue of Wilberforce can be seen in the North Choir Aisle, close to where we first came in. It shows him seated, and the inscription pays him honour, not just as the prime campaigner against slavery, but as one ....who fixed the character of their times..., reflecting his role in changing the attitude of Britain from the selfishness and cruelty of the eighteenth century to the greater responsibility of the nineteenth.

As we leave, there are memorials to two men who both waged lifelong battles against poverty, cruelty and degradation in Victorian England, but used very different techniques. In St George's Chapel, to the left of the west door, is a marble bust of William Booth, with the inscription Founder and first general of the Salvation Army 1829-1912 in gold lettering. The untiring efforts of the Army against poverty and injustice have continued for nearly 150 years, and their brass bands and uniforms are known across the world.

Just to the right of the west door stands a statue of Anthony Ashley Cooper, seventh Earl of Shaftesbury. The inscription Endeared to his countrymen by a long life spent in the cause of helplessness and suffering hardly does justice to his achievements. As a conservative aristocrat, Shaftesbury was an unlikely philanthropist, but his Christian commitment was no pretence. His efforts to ease the lot of women and children in factories, and his support for every effort to alleviate suffering and improve education were honoured in his time but largely forgotten today. His chief memorial is the Angel of Christian Charity in Piccadilly Circus. Most people call it Eros!

ST MARGARET'S WESTMINSTER

St Margaret's, Westminster

Between the Abbey and Parliament Square stands St Margaret's, the parish church of the House of Commons, used for weddings, baptisms and funerals of politicians past and present. Winston Churchill was married here in 1908. We pass it as we stand in the queue for the abbey, but it is an impressive building in its own right, despite being overshadowed by its more illustrious neighbour.

A stained glass window at the west end commemorates John Milton, who was a parishioner and whose wife and child are buried here. It shows the blind poet dictating verse to one of his long-suffering daughters, quill pen in hand. The window was presented by George W Childs of Philadelphia, who felt that Milton's writing on freedom of speech and religion had made a significant contribution to American independence.

In the south aisle is a plaque to Phillips Brooks, Bishop of Massaschusetts, best known as author of the Christmas carol O Little Town of Bethlehem.

HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT

Oliver Cromwell

Immediately across the road from the Abbey is Westminster Hall, the oldest part of the Palace of Westminster, built originally by William Rufus, son of the Conqueror. Here stands a defiant Oliver Cromwell, sword in one hand and Bible in the other, sculpted by Sir Hamo Thorneycroft in 1899. His relations with Parliament were ambivalent to say the least. He fought and won a Civil War to defend its rights against the abuses of Charles I, whom he brought to trial here in Westminster Hall. But when that was done and Parliament threatened to disband his army, he expelled it and ruled as Lord Protector - a virtual dictator.

To the south of the main palace complex lie Victoria Gardens, a pleasant space for lunchtime sunbathers and television reporters interviewing politicians. Here there is a strange neo-Gothic commemorative fountain, like a miniature Albert Memorial. It was erected in 1866 to the anti-slavery campaigner Thomas Fowell Buxton, but also mentions a few of his fellow abolitionists.

LAMBETH PALACE

Lambeth Palace

Immediately across the river from Victoria Gardens is Lambeth Palace, official residence for many centuries of the Archbishop of Canterbury. This causes some confusion to tourists who feel, not unreasonably, that he ought to live in Canterbury.

It is not normally open to the public, but access to historic documents from the library is sometimes provided for special exhibitions. These include the McDurnan Gospels produced by monks in Ireland in the 9th century, the 12th century Lambeth Bible and a printed Gutenberg Bible of 1455. There are also other items that have come into the possession of the Archbishops in the course of their official duties, including the gloves worn by Charles I at his execution.

WESTMINSTER CHAPEL

Westminster Chapel

Sited In Buckingham Gate, not far from the Palace, the chapel has been a focus of evangelical preaching and ministry for 180 years. Founded in 1841 in what was then one of London's poorest slums, the church's early ministry, under Rev Samuel Martin, was much involved with caring for orphans and providing work for the unemployed. The present building in Romanesque revival style dates from 1865.

In the 20th century, the church became a centre for Biblical teaching under three outstanding ministers, George Campbell Morgan (1863-1945), Dr Martyn Lloyd Jones (1899-1981) and Dr R.T. Kendall. Campbell Morgan served two periods as pastor, 1904-17 and 1933-43, his earlier ministry and the intervening years being spent mainly in America, originally in association with the evangelist D.L. Moody. He was also a prolific author.

In 1914, Lloyd Jones's father moved his family from rural Wales to Westminster to start a grocery business, and during the First World War the teenaged Martyn would help with milk deliveries around the area, while continuing his education and in spare moments going to hear his eloquent Welsh compatriot David Lloyd George speaking in the House of Commons. Naturally gifted, he decide to become a doctor and a distinguished medical career beckoned when he became assistant to the King George V's physician Sir Thomas Horder.

Feeling a strong call to the ministry, he abandoned medicine and served 12 years as pastor of Sandfields Chapel in Aberavon, near Port Talbot. In 1938, Lloyd Jones returned to Westminster as assistant to Campbell Morgan, taking over as minister in 1943, until he retired in 1968. During this period, his deep expository preaching became famous internationally, and sermons would be published - sometimes requiring several volumes to cover one New Testament epistle! He also rediscovered the Reformed doctrines of the Puritans and promoted their publication of their works for a new generation of Bible students. A firm believer in independent church government, he caused controversy by encouraging evangelical Anglicans to leave the established church, but with only limited success.

VICTORIA EMBANKMENT

William Tyndale statue

From the Houses of Parliament, the Embankment Gardens lie northwards along the river. They are in two parts, bisected by Charing Cross railway bridge, and colourful with flowers and shrubs in summer. In the first garden is a statue of Bible translator William Tyndale (1494-1535), magnificently capped and gowned as a sixteenth century scholar. A cumbersome looking printing press stands at his side. The inscription tells us of Tyndale's last prayer, as he was burned at the stake in Vilvorde, Belgium, Lord, open the king of England's eyes, and how it was answered a year later by the placing of the English Bible, Tyndale's life work, in every parish church by the king's command.

Robert Raikes statue

Passing under the bridge, at the far end of the next garden we find Robert Raikes, the Gloucester printer, generally recognised as the founder of Sunday Schools in 1780, though not without a few rival claimants. The statue was erected in 1880 to mark the centenary, paid for by subscriptions from Sunday School teachers and children.

WEST STREET CHAPEL

West Street chapel

Squeezed between Long Acre and Shaftesbury Avenue is a network of streets, where many eighteenth century terraces have survived. At 24-26 West Street is a building of yellowish brick of great interest in the early history of Methodism. Originally a Huguenot chapel built in 1700, it was occupied by the Methodists from 1743 to 1798. A blue plaque on the wall records that John and Charles Wesley preached here frequently and there are many references in John Wesley's diary. The building is currently used as offices by several design companies. It still has arched sash windows in eighteenth century style.

ORANGE STREET CHAPEL

Orange Street chapel

Another chapel to have survived bombs and bulldozers for over 300 years is in Orange Street, just behind the National Gallery. A semicircular inscription over the door has the words Orange Street Chapel 1693-1929, but it still functions as a Congregational church. The building began as a French Calvinist church, and from 1775 until his death three years later the minister was Augustus Montague Toplady, author of Rock of Ages. Jemima Luke, who wrote the children's hymn I think when I read that sweet story of old was a Sunday School teacher here.

TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD

Not so fortunate as the other chapels was George Whitefield's Tabernacle, originally built in 1756 as a centre for Whitefield's work in west London. It was damaged by fire in 1857 and rebuilt in 1903, only to be destroyed by one of the last V2 missiles to hit London in 1945. An uninspiring red brick building, the Whitefield Memorial Church, opened in 1957, now stands on the site and is used by an American congregation. There used to be a plaque on the outside north wall recording that Augustus Toplady was buried in the original chapel in 1778. The open space alongside, known as Whitefield Gardens, has a series of display panels telling the story of the Tabernacle and other events and personalities associated with the area.

LANGHAM PLACE

All Souls Church

Forming a short dog-leg between the north end of Regent Street and Portland Place, Langham Place is the location of Broadcasting House, headquarters of the BBC, and also All Souls Church (W1B 3DA), whose distinct profile often provides the backdrop for an outside interview or broadcast.

Designed by John Nash and opened in 1824, the church's unusual style features a circular vestibule supported by Grecian columns, approached by tiers of steps, which provide a convenient spot for local workers to sit and eat their sandwiches. Above the vestibule, the spire emerges from another circle of columns.

For over 60 years, the Rev Dr John Stott (1921-2011) was associated with All Souls, first as curate from 1945, then rector from 1950 to 1975, and finally as Rector Emeritus, while engaged on many international projects. Stott became the principal spokesman for evangelical Anglicanism in the second half of the 20th century and gained a worldwide reputation for his writing and teaching. He wrote over 50 books, led university missions in Britain and America and in 1974 played a leading role at the International Congresss on World Evangelisation in Lausanne, helping to draw up the Lausanne Covenant that emerged from it. While serving here, Stott, a lifelong bachelor, lived nearby at the church's rectory, 12 Weymouth Street.

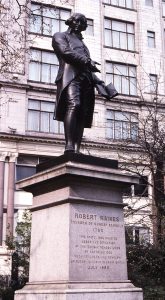

Leading off from Langham Place is the narrow Riding House Street, and towards the far end, a plaque on a university building records that this was the site of the home of Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797).

Olaudah Equiano plaque

In a life full of adventure, Equiano was born on Benin, Nigeria, captured as a child and sold as a slave in Virginia. He was bought by Michael Pascal, a Royal Navy officer, who renamed him Gustavus Vassa and served with him through the Seven Years War (1756-63). Sent to England for education, he came under the influence of George Whitefield, converted to Christianity and was baptised at St Margaret's, Westminster. Despite this, he was sold on and bought by Robert King, a Quaker businessman in Philadelphia. King allowed him to trade independently and eventually buy his freedom, even offering him partnership in the business.

After further adventures, Equiano settled in London and from 1780 became increasingly involved with the Abolition movement, in association with figures such as Granville Sharp and Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. In 1789 he published The Interesting Life of Olaudah Equiano, the African, which became a sensation across Europe as the first personal account of slavery. In 1792, he married Susannah Cullen, and fathered two daughters.

GREAT ORMOND STREET

John Howard's house

The world famous children's hospital covers almost the whole of the north side of the street. Immediately opposite at Number 23 is a handsome white-painted house, once the home of the prison reformer John Howard (1726-1790). Howard was appointed High Sheriff of Bedford in 1773 and, shocked by the state of prisons in his own county, he began a campaign of reform which extended across the whole of Europe.

PICCADILLY CIRCUS

Eros

The statue of Eros, wrought by Sir Alfred Gilbert in 1892, is an iconic landmark of London and famous across the world. What is not well known is that it is not Eros at all but the Angel of Christian Charity, a memorial to Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885). Shaftesbury was a Tory aristocrat, whose practical Christian faith took him above party politics. In a lifetime of philanthropic effort, he campaigned for improvements in factory conditions, slum clearance, protection of child workers, education and reform of lunacy laws. Those who can wade through the tourist throng will find a bronze inscription to Shaftesbury around the base.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

Just behind the National Gallery is the National Portrait Gallery with the entrance in St Martin's Lane. Its aim is to acquire and display contemporary portraits of famous men and women throughout British history. This unique collection includes images of most of the people covered in this guide, the earliest an impression of Alfred the Great on a silver penny. Contemporary authenticity is valued more than artistic merit and, for some, the portrait here may be the only known likeness in existence.

John Wesley

Whether or not the portraits you might wish to see are on display is another matter. Inevitably, only a small proportion can be shown at any one time and if you come intent on seeing a particular work, prepare to be disappointed. To compete as a visitor attraction, the Gallery is more likely to fill its wall space with avant garde images of pop stars and celebrities than eighteenth century divines!

When we called, the Tudor gallery on the second floor displayed martyr-bishops Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, both by unknown artists, and the well-known 1546 portrait by Gerlach Flicke of Thomas Cranmer, looking somewhat younger than his fifty-seven years at the time. In the rooms devoted to the Stuart period was the 1649 portrait of Oliver Cromwell by Robert Walker. He is shown in a suit of armour, with the final adjustments being made by a servant. An adjoining room, devoted to the circle of Samuel Pepys, had a small picture of John Milton by an unknown artist. It conveys the delicate complexion for which Milton was known as a young man; it dates from about 1629, when he was twenty-one.

In the eighteenth century section are portraits of the principal figures of the evangelical revival, including perhaps the best known image of John Wesley- book in one hand, the other raised in preaching - painted by Nathaniel Hone in 1766. George Whitefield, by John Woolaston, has a strange expression, arms outstretched as if about to dive into the congregation. The star struck lady sitting in front is said to be his wife. There is also the Countess of Huntingdon, by an unknown artist about 1770, and an interesting group portrait of members of the Moravian Brethren, including Count von Zinzendorf.

John Bunyan

In a large gallery called the Road to Reform, the well- known unfinished portrait of William Wilberforce by Sir Thomas Lawrence was grouped with pictures of Sunday School pioneers, Robert Raikes, Hannah More, and Sarah Trimmer. Here too is the massive painting by Benjamin Haydon of the 1840 meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society. It is being addressed by the aged and frail Thomas Clarkson who had by then been active in the movement for fifty-five years. Most of the picture shows row upon row of delegates and a contemporary critic's description of it as a wagon-load of Quaker heads has some justification. Among the assembled gentlemen are a small number of ladies in Quaker bonnets, mostly at the back, and also a few black faces, including the freed slave Henry Beckford sitting prominently in the foreground.

In the galleries covering the Victorian period, there were many bewhiskered gentlemen, but it seems they could find no room for the rather stony-faced image of David Livingstone by Frederick Havill, nor for Ingles famous portrait of General William Booth of the Salvation Army. However, they managed to squeeze in an 1862 panel of the philanthropist Lord Shaftesbury, in a room devoted to portraits by G. F. Watts.

All visitors will have favourite pictures they would like to see displayed, and may be frustrated at their absence. For me, the omission of Thomas Sadler's famous portrait of John Bunyan was the biggest disappointment. The status of any particular portrait can be checked on the gallery's website.

[Images courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London]

MARYLEBONE

Charles Wesley memorial

In 1771, Charles Wesley (1707-1788) returned to London from Bristol to help his brother in the capital, and lived the remainder of his life at what was then 1 Great Chesterfield Street, with his musically gifted family. The house has gone but a blue plaque on the King's Head pub, on the corner of Wheatley Street and Westmoreland Street, marks the site. A nearby street is called Wesley Street in his honour. His home became the scene of subscription concerts given by his children and attended by Dr Johnson and other members of fashionable society. John Wesley also came rather reluctantly, finding himself ill at ease in such company.

At a time when Methodism was gradually drifting towards dissent, Charles Wesley was a loyal Anglican to the last. Spurning the offer of a resting place in the unconsecrated ground of his brother's City Road Chapel, he famously declared I will be buried in the yard of my parish church, and was. In March 1788, perhaps the greatest hymn writer of all time died at his home, and was laid to rest in the churchyard of Marylebone Old Church. The church was finally demolished in 1949 but a small obelisk to the great poet of Methodism is the central feature of a peaceful memorial garden in Marylebone High Street. It has a verse of praise to Charles, and also remembers his wife Sarah who lived to the remarkable age of ninety-six. The large Church of St Marylebone, in the classical style, which faces the busy traffic on Marylebone Road was built in 1817 to serve the needs of the growing parish.

BROOK STREET MAYFAIR

Handel's house

Number 25, not far from the junction with New Bond Street, was the home of the composer George Frederic Handel from 1723 until his death and carries the familiar blue plaque. It was here that he composed the sublimely beautiful Messiah in a frantic spell of twenty-three days in 1741 and it was here he died in 1759. After completing the triumphant Hallelujah Chorus, he was found in tears by his servant declaring that He had seen the heavens opened and the great God Himself. The texts of the great oratorio were compiled by Charles Jennens, a wealthy amateur, who acted as librettist for several of Handel's works.

The top three floors of the building form the Handel House Museum, which is entered from the rear via Lancashire Court. A short video tells the story of the composer's life and work. The rooms are uncarpeted and there is little contemporary furniture, but the walls are covered with portraits of Handel and his associates together with pictures and prints illustrating 18th century London life.

ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

Livingstone statue

On the corner of Kensington Gore and Exhibition Road are the oddly misshapen headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society. From a recess halfway up the wall, the statue of David Livingstone (1813-1873) surveys the passing traffic as he once surveyed the plains of Africa or the waters of Lake Nyasa. The society has many of Livingstone's personal possessions and items from his expeditions.

CADOGAN PLACE

Wilberforce plaque

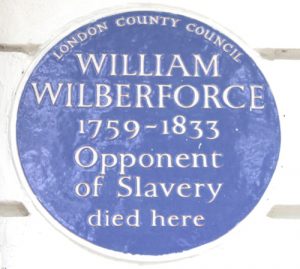

In this terrace of handsome, white-fronted houses off Sloane Street, No 43b carries a blue plaque stating simply that this was the house where William Wilberforce died in 1833.

Wilberforce had lived for many years at Hyde Park Gate, not far away, where his children spent their formative years. As advancing age took its toll, he had been staying with his sons in their country rectories. On 19th July 1833, in poor health, he journeyed from Bath to the London home of his cousin Lucy Smith. On 26th July, he heard news of the climax of his life's work, when the House of Commons passed the third reading of the Abolition of Slavery Bill. He died three days later.

FULHAM

Granville Sharp's grave

At the north end of Putney Bridge is All Saints Church and in the churchyard lies Granville Sharp (1735-1813), one of the unsung heroes in the fight against slavery and all its works. His tomb lies close to the gate leading to Fulham Palace, home of the Bishops of London. The inscription on the front, badly weathered, refers to his brother and sister, but on the back Sharp's epitaph was restored to mark the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade. It refers to his career of almost unparalleled activity and usefulness and that his efforts deserve to be remembered as long as ......homage shall be paid to those principles of justice, humility and religion

Sharp's specific contribution to the abolition movement involved a slave called Jonathan Strong, whom he befriended in 1765, after finding him abandoned and destitute in London. Strong's "owner" David Lisle had Strong thrown into prison, but Sharp brought a counter charge and had Lisle prosecuted for assault. In 1772, the issue was finally settled by the case of another slave - James Somersett - for whom Sharp obtained the historic legal ruling that as soon as any slave sets foot on English territory, he becomes free. As the parish church for Fulham Palace, the churchyard has the tombs of at least seven former Bishops of London.