Kent

CANTERBURY

With its medieval street pattern, its status as a World Heritage Site and its Cathedral, Canterbury is a major destination for tourists, including many who come to explore its Christian heritage.

The story begins in Rome in the sixth century. As a young deacon, the future Pope Gregory saw some fair-haired boys in the Roman slave market. On enquiring what race they were, he was told they were Angles. Impressed by their appearance, Gregory replied Non angli, sed angeli - not Angles but angels! A mission to the land of the Angles became his lifelong ambition. At first he wanted to lead it himself and persuaded Pope Benedict to let him go, but other duties intervened and the expedition never materialised.

Pegwell Bay

Some thirty years later Gregory was pope and in 596 he appointed Augustine, prior of St Andrew's monastery in Rome (not to be confused with the earlier St Augustine of Hippo), to lead a mission for the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England. Augustine set out with forty monks, but halfway there they lost heart and returned to Rome. Gregory encouraged them to continue, providing Frankish interpreters and letters of introduction, and promoting Augustine to the rank of Abbot. They set off again and landed at Pegwell Bay on the Isle of Thanet in 597. Augustine sent emissaries to King Ethelbert of Kent, whose French wife Bertha had been converted to Christianity before her marriage. She had brought with her a priest called Luidhard and for nine years had been worshipping with members of her household.

Ethelbert received the monks politely but cautiously. He listened to Augustine's message and allowed him to proceed to Canterbury to preach there without hindrance. Today the place of this first encounter is marked by a cross at Cliffsend, erected in the nineteenth century. A few months later Ethelbert accepted the new faith and was baptised and Augustine then travelled to Arles in France to be consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury. He also sent two of his helpers, Laurentius and Peter, to Rome to report on what had been achieved. In 601 they were back, bringing reinforcements in the form of three monks, Mellitus, Justus and Paulinus, who were to have great significance in the early years of the English church. Mellitus became the first bishop of London and Justus first bishop of Rochester, while Paulinus accompanied Ethelbert's daughter Ethelburga to York as bride to the Northumbrian king Edwin.

St Martin's Church

St Martin's Church

Church historians seldom agree on superlatives, especially when local pride is at stake, but there is general acceptance that St Martin's, Canterbury, is the oldest church in Britain. The Roman bricks built into its walls are reckoned to be from the church in which Queen Bertha worshipped, while Ethelbert was still offering his devotions in a pagan temple which later became St Augustine's Abbey. It is probably the only church in England that can claim 1,400 years of continuous Christian worship.

The church (CT1 1QJ) is in North Holmes Road, off Longport, about a mile east of the city centre. It is open for limited periods during the week. With such historic importance and tourist interest, it must be hoped that these times can be extended. We can study the church from outside, but even here the view is restricted by surrounding trees. The Roman brickwork can be clearly seen and it is probable that the western end of the chancel formed part of Queen Bertha's church while the nave was added soon after Augustine's arrival. Later stained glass windows show scenes from the early history of the English church.

A notice at the church gate quotes a passage from Bede referring directly to St Martin's, and the display board in the churchyard gives useful information on the whole site including St Augustine's Abbey nearby.

St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine's abbey

According to tradition, this was the site of King Ethelbert's pagan temple, which he handed over to Augustine after his conversion for the construction of a monastery. Apart from the medieval Fyndon Gate in Monastery Street, the site is now a mass of ruins but impressive nonetheless (CT1 1PF). As with most foundations, the monastic buildings grew in prosperity and size throughout the middle ages, but their fortunes came to an abrupt halt with the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in 1538. From then on the site was pillaged as a source of materials for other buildings, including Henry's castles around the Kent coast. In the early nineteenth century, the area had become the site of a brewery and pleasure garden but was purchased for more appropriate use by Alexander Beresford Hope, a local MP, part of it forming a missionary college.

There is a modern exhibition centre, telling the history of the Abbey from the time of Augustine. Originally designated the Abbey of St Peter and St Paul, it was re-dedicated to St Augustine by Archbishop Dunstan in 978. The exhibits include many artefacts recovered from the site.

Site of Augustines's grave

In the centre of the abbey grounds, a canopy covers the site of the original Saxon foundation. Here again we can see the use of re-cycled Roman bricks and tiles. This was the burial place of the early archbishops of Canterbury and stone plaques mark the presumed graves of Augustine (in office 597-605), Laurentius (605-619), Mellitus (619-624) and Justus (624-627). Another plaque marks the grave of Theodore of Tarsus, a citizen of St Paul's native town who became archbishop in 669 at the age of about 66 and whose wisdom and experience guided the church through turbulent times. He died in 690 at a remarkable age.

The Cathedral

For a full description, the visitor should consult one of the official guides available from the bookstall. The original cathedral replaced a ruined Roman church given to Augustine by King Ethelbert. Parts of the present cathedral date from the rebuilding by Archbishop Lanfranc after the Norman Conquest, but most is from the fourteenth century. The impressive Christ Church Gate, leading into the cathedral precincts was built in 1517-1520 as a memorial to Henry VIII's deceased brother Arthur.

Cathedral gatehouse

At the west end of the north aisle is a list of all the Archbishops from the time of Augustine to the present day. Their names recall some of the most dramatic episodes in English history: Thomas a Becket and his ill-fated defiance of Henry II; Stephen Langton, whose wise counsel persuaded King John to sign the Magna Carta; and William Laud, whose attempt to bring back ritual to the Church of England and to impose the Prayer Book on the Scots angered the puritans and helped to provoke the Civil War.

In Shakespeare's Richard II, the king meditates mournfully on the death of kings, Some murdered by their wives, some sleeping killed..... He might equally have pondered the gruesome fate of several Archbishops of Canterbury: Laud executed on the block and Thomas Cranmer burned at the stake; Simon of Sudbury, beheaded by a mob on Tower Hill during the Peasants Revolt; the saintly Alphege beaten to death with ox bones by the Danes in a drunken orgy at Greenwich; and, most famous of all, Thomas a Becket, the "turbulent priest" struck down by four knights within the cathedral walls at the behest of Henry II.

Canterbury Cathedral

Only one king is buried in the cathedral. Henry IV (Bolingbroke in Richard II) lies here, together with his uncle the Black Prince, whose personal armour is also on display. Both are in the Trinity Chapel towards the east end. Here too is the plain tomb of Cardinal Coligny, who fled France because of his Huguenot sympathies and is said to have been murdered by a servant who gave him a poisoned apple. The French connection continues to this day with part of the crypt in use as a French Protestant church. Also in the crypt are two columns brought from the Saxon monastery at Reculver on the north Kent coast, dating from the time of Theodore of Tarsus.

Many of Canterbury's archbishops lie within the cathedral walls. They include two saints from Saxon times, Dunstan and Alphege. Their shrines have gone but they are remembered by inscriptions close to the High Altar and window medallions show scenes from their lives. Dunstan (924-988) became Abbot of Glastonbury at the age of 21 and was later Bishop of London and Bishop of Worcester. In 961 he became Archbishop and travelled to Rome to be consecrated. He helped to integrate the Danes into the political life of the country and to unify the nation under King Edgar. Alphege (953-1012) became Bishop of Winchester in 984, at a time when Viking invasions were again threatening the country. He was involved in embassies to persuade the invaders to honour their former pledges, but his efforts were undermined by the weakness of King Ethelred "the Unready". In 1005 he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury but in 1011 the Danes attacked Canterbury, dishonouring former treaties, and he was captured. Held prisoner for seven months by his captors in the hope of a larger ransom, Alphege refused to be ransomed when he saw how this would beggar the people. On 19th April 1012, he was pelted to death at a drunken feast in Greenwich, the site now marked by a church in his name.

Other archbishops buried here include the headless Simon of Sudbury (his head is at his home town in Suffolk!), Henry VIII's William Warham, William the Conqueror's Lanfranc, King John's Stephen Langton and Mary Tudor's unlamented Reginald Pole.

One who lies here no longer is Thomas a Becket (1118-1170) who became Chancellor to Henry II in 1155 and Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162. His conflicts with the king came to a head in 1170 when he was murdered by the four knights, responding to Henry's cry to be rid of the turbulent priest. The place is marked by a modern sculpture in the north-west transept. Becket became Chaucer's holy blissful martyr and his shrine was the destination of those Canterbury pilgrims, telling their tales along the Pilgrims' Way. The tomb was a marvellous thing, adorned with gold and rubies, and the scene of many supposed miracles. At the Reformation, all was swept away as idolatry and superstition, while believers turned instead to the newly translated scriptures for guidance and comfort.

CLIFFSEND

St Augustine's cross

About a mile inland from Pegwell Bay is a monument marking the arrival of St Augustine in this area in 597. It is on the edge of a field in Cottington Road (CT12 5JN) close to St Augustine's Golf Club! In the form of a Celtic cross, it was erected in 1844 by Earl Granville, Lord Warden of the Cinq Ports. The Latin inscription (fortunately with English translation) tells us that it was near this spot that Augustine met King Ethelbert and preached his first sermon on English soil.

RECULVER

Saxon Church, Reculver

This remote spot on the north Kent coast was sufficiently isolated to be used as a testing site for bouncing bombs in the Second World War. Overlooking the grey waters of the Thames estuary is a ruined Saxon church with its distinctive square towers linked by a pointed gable. The only other prominent building is a pub called the King Ethelbert Inn (CT6 6SU). The king in question retired here around 610 after presenting his palace at Canterbury to Augustine. In 669, King Egbert of Kent gave the site of a Roman fort for the foundation of a monastery, which was later granted to the Archbishop of Canterbury. A seventh century cross from here can be seen in the crypt of Canterbury Cathedral. On a grassy patch opposite the pub, a millennium cross celebrates 2000 years of Christianity.

ROCHESTER

Rochester Cathedral

Strategically placed on the river Medway, Rochester was important to the Romans and later to the Normans who built the castle, of which the outer walls survive reasonably intact. It was also the home of Charles Dickens, featuring in several of his novels, and local businesses trade heavily on the connection, many with Dickensian names.

After being well received by King Ethelbert at Canterbury in 597, Augustine sought to expand his mission westwards and in 604 founded bishoprics at Rochester, where Justus was appointed first bishop, and at London. Rochester is thus reckoned the second oldest diocese in England. The present Cathedral (ME1 1SX) was begun by the Normans and altered or extended several times during the medieval period. The stumpy spire with its blue clock faces and herringbone pattern forms a prominent landmark. Nothing remains of the original Saxon cathedral, although its foundations have been located at the west end of the nave.

In 633, Paulinus, who had led a mission from Canterbury to King Edwin of Northumbria, had to flee when Edwin was killed at the Battle of Hatfield Chase. He brought Edwin's Christian queen Ethelburga, the daughter of Ethelbert and Bertha, back to Canterbury with her children. He had originally escorted Ethelburga to York as bride for the pagan Edwin, who subsequently embraced her faith. Paulinus was appointed bishop of Rochester in 635 and was buried in the cathedral when he died in 644. His successor was Ithamar, the first Anglo-Saxon to be made a bishop.

In the nineteenth century, a screen was built depicting eight important figures in the life of the cathedral. They include Ethelbert, Justus and Paulinus as well as various medieval bishops. Controversially, the figures also include the catholic Bishop John Fisher, executed for refusing to acknowledge Henry VIII as head of the Church of England, but not the protestant Nicholas Ridley, bishop in the time of the boy king Edward VI. Ridley went on to become Bishop of London and was responsible for the foundation of many schools and hospitals but suffered a martyr's death on the accession of Edward's half-sister Mary. Ridley's only memorial in Rochester appears to be a tablet on the wall of the Baptist Church in Crow Lane. However, the two martyrs are given equal prominence in the cathedral guide book, which reproduces the well-known woodcut of the burning of Latimer and Ridley at Oxford.

GRAVESEND

We come here in search of a winsome young lady, who is celebrated as the first native Christian convert in North America, and more recently as the heroine of a Disney cartoon adventure.

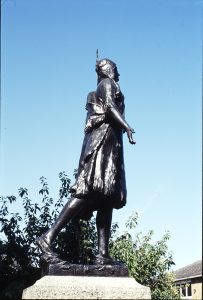

Pocahontas statue

Pocahontas (1595-1617) was the daughter of Powhatan, the warlike chief who repeatedly threatened the survival of the English colony of Jamestown in Virginia. Unlike her father, she was fascinated by the new arrivals, and they with her. On two occasions she intervened to save the life of Captain John Smyth, their swashbuckling commander. She later married John Rolfe, one of the settlers and bore him two sons, ushering in a period of peace between the two communities.

In 1616, she sailed for England with her husband and a retinue of fellow "Indians". They caused a sensation in London society, were received at court by James I and taken to see a play by Ben Jonson. Awaiting return to Virginia, Pocahontas was taken ill on board ship off Gravesend and died. Her body was brought ashore and buried with honour in the chancel of St George's Church on 21st March 1617.

The church was destroyed by fire a hundred years later, but rebuilt in the Wren style in 1732, the tower with a short white-painted spire and blue-faced clock. The churchyard is now called Princess Pocahontas Gardens (DA11 0DJ) and has a statue of the young heroine cut down in the prime of life, with a feather in her hair and arms outstretched in a gesture of peace. A display board by the shopping centre entrance tells her story.

SHOREHAM

Shoreham Church

Not to be confused with its seaside namesake in Sussex, the village is tucked away in the Darent valley just north of Sevenoaks. It has rose-covered cottages, ancient inns and an old bridge. Vincent Perronet (1693-1785) came here as vicar in 1728 and remained for an astonishing fifty-seven years. He was one of John Wesley's earliest and most faithful supporters among the established clergy. Wesley trusted him absolutely and sought his advice on many matters. One piece of advice he would have done better to ignore, for the good rector recommended him to marry the widowed Mrs Vazeille; the marriage proved an unmitigated failure. When the old rector died in peace and joy at the age of ninety-one, Wesley wrote in his diary O that I might follow him in holiness; and that my last end might be like his.

The Church of St Peter and St Paul is faced with brick and flint and approached through an avenue of yew bushes (TN14 7 SB). A marble tablet on the north wall commemorates Perronet, but the inscription mainly describes the spiritual conflicts of his wife. Referring to the long-serving rector, we are encouraged to be followers of him, even as he was of Christ. Two of his sons became itinerant preachers with Wesley and Edward Perronet (1726-1792) was author of All hail the power of Jesus name, which ranks with the best of Charles Wesley's hymns.

A picture on the west wall illustrates the triumphant return of Verney Lovett Cameron to the village in 1876, having led the first east-west crossing of the continent of Africa. Cameron, son of the incumbent vicar, set out to find David Livingstone and met the sad procession of the explorer's two servants Susi and Chuma carrying his body. He continued his journey to find Livingstone's hut and rescued his last diaries and papers, which he sent home to Livingstone's sister.

Another resident of Shoreham was the religious artist Harold Copping (1864-1932) whose illustrations brought the Bible and Pilgrim's Progress to life for young and old alike. He lived in Shoreham for thirty years and is buried in the churchyard. There is a commemorative brass plaque on the west wall.

TESTON

James Ramsay memorial

The church of St Peter and St Paul overlooks a pleasant fruit-growing valley not far from Maidstone (ME18 5BY). On the outside wall is an epitaph to James Ramsey (1733-1789), who came here as vicar in 1781. In the flowery language of the day, it praises his firm integrity, unaffected zeal for the public good, steady contempt for self-interest, tender attention to each social duty .... Facing it across the churchyard is a memorial to his black servant, a freed slave called Nestor. The inscription is badly eroded, but the full text is recorded inside the church. It makes the point that by his industry and character Nestor helped to disarm contemporary prejudices against his race.

Ramsay had trained as a naval surgeon, but an accident lamed him for life and he took Holy Orders. He served as a chaplain in the West Indies, and acted as both doctor and pastor to slaves on the plantations. Appalled by what he saw, he became a zealous opponent of slavery and all its works. He later became a naval chaplain and saw action in several engagements. When he arrived at Teston, his neighbour at Barham Court, next door to the church, was Admiral Sir Charles Middleton, later Lord Barham. Having served in the admiral's fleet, he found Middleton a firm friend and supporter. Through his influence and connections, Ramsey was able make known what he had witnessed to those in authority, including William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Hannah More and the Prime Minister William Pitt. For a time the vicar of Teston bore the burden of the abolition movement almost single-handed, but in due course it gathered relentless momentum.

KESTON

Wilberforce Oak

Holwood House near Keston was once the country home of the young prime minister William Pitt. Visiting him here in 1787, his friend and colleague William Wilberforce raised the question of the slave trade in a conversation beneath an oak tree on the estate. I resolved to give notice on a fit occasion in the House of Commons of my intention to bring forward the abolition of the slave trade, he later recalled in his diary. It was to be twenty years before the Abolition Bill was finally passed, by which time Pitt, prime minister for nearly all that time, was dead.

The Wilberforce Oak, or what remains of it, can be seen on a path through the Holwood estate. Using the Keston Ponds car park (BR2 6 AT), take the footpath south through the wood, then cross the busy A233 and continue on the gravel path for about half a mile. The original tree is now just a rotting stump but a new sapling has been planted to replace it. Trees to the south have been cleared to give an idea of the view the two politicians would have enjoyed.

WESTERHAM

Westerham has such a surfeit of heroes that it seems almost to have forgotten the one we are seeking. James Wolfe, the victor of Quebec, was born in the village and Winston Churchill's much loved home of Chartwell is less than a mile away. Both have statues on the green.

John Fryth's birthplace

We come in search of John Fryth, scholar and Protestant martyr, who was born here in 1503. The son of an innkeeper, he attended Eton and King's College, Cambridge. His scholarship attracted the attention of Cardinal Wolsey, but he adopted Protestant views and fled abroad to help William Tyndale with his Bible translation. He wrote a treatise refuting the views of Sir Thomas More on the nature of the eucharist, contending that the body of Christ was in heaven and could not be in two places at once. On his return to England he was arrested and held in the Tower, before being burned at Smithfield on 4th July 1533.

There is no statue to Fryth, but here on the green is his birthplace, formerly the White Horse inn, now a private house (TN16 1AS). It is immediately to the left of the churchyard entrance, white-painted, with two dormer windows and steps up to the front door. The age of the building can be better appreciated by examining the ancient brickwork from the churchyard. In St Mary's Church, the John Fryth Room was added in 1969.