Buckinghamshire

OLNEY

The broad main street of Olney comes to life each year with a Shrove Tuesday pancake race between the ladies of the town and those of Liberal, Kansas, in America.

Olney Church

Olney's most famous residents, still remembered after 250 years, were John Newton (1725-1806) and William Cowper (1731-1800). They came from backgrounds as far removed as possible, but their improbable friendship produced some of the most sublimely beautiful hymns in the English language.

Newton, son of a merchant navy captain, went to sea at the age of eleven and rose to command a slaving ship while still in his early twenties. In the course of an adventurous career he was press-ganged, flogged and at one point even reduced to virtual slavery himself as servant of the African mistress of another slaving captain. Hearing George Whitefield preach in America, Newton's conscience was awakened and at the height of a storm at sea he cried out to God for mercy. Renowned for blasphemy and licentiousness during his early years, Newton summed up his experiences in the famous lines:

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me

I once was lost but now am found

Was blind but now I see

The Cowper-Newton Museum

Leaving the sea, he worked initially as a tide surveyor in Liverpool before being ordained. He arrived in Olney in 1764, as curate to the absentee vicar Moses Browne, and remained for sixteen years. Newton later became a leading opponent of slavery and was able to provide William Wilberforce and others with first hand evidence of the evils of the trade.

William Cowper, gentle, timid and subject to bouts of black depression, trained as a lawyer but his mental state precluded regular work and he settled in Olney in 1767, cared for by a devoted widow, Mary Unwin (1724-1796). He loved the things of the countryside - hares, birds and flowers. His poems ranged from the comical John Gilpin to the semi-autobiographical The Task, with its poignant lines:

I was the stricken deer that left the herd

Long since, with many an arrow deep infixed

My panting side was charged when I withdrew

To seek a tranquil death in distant shades

There I was found by one who had himself

Been hurt by archers. In his side he bore

And in his hands and feet the cruel scars.

With gentle force, soliciting the darts

He drew them forth, and healed and bade me live.

We don't have to look far for memories of the two friends. There is a Cowper Memorial Church in the High Street in an unattractive late Victorian style. Even the public toilets in the Market Place have a weather vane showing Cowper in his armchair, with pet hares frolicking around his feet. Here too is Orchardside, the three-storey red brick house where Cowper lived from 1768 to 1786, now housing the Cowper-Newton Museum (MK47 4AJ).

The Hareflap

From the front the house looks uniform, but from behind it appears as two cottages with a linking wall. The left half of the building is mainly concerned with the town's former lacemaking industry. Items relating to Cowper and Newton are in the right hand section which we enter from the back. The kitchen leads through to the hall and linking the two is a hatch like a catflap, through which the poet's pet hares used to pass. A stuffed hare sits here by way of illustration. The hall has portraits of Cowper's parents and other family items. The next room was Cowper's sitting room and has his grandfather clock and contemporary prints and pictures.

Slave ship model

The room leading off the stairs is devoted to John Newton. It has a cut-away model of a slaving ship and visitors automatically trigger a tape of appropriate seafaring noises. Pictures of Newton, his Bible and letters to his wife are on display. Another portrait is of William Bull, a friend and fellow minister from Newport Pagnell.

On the first floor is Mary Unwin's bedroom, now called the Costume Room, with a display of contemporary clothing. Next door is Cowper's bedroom with a sequence of pictures illustrating his humorous poem John Gilpin. There is also an electrical machine used to treat Mrs Unwin when her right arm and hand were paralysed by a stroke.

Garden and hymn factory

The gardens have been painstakingly restored to include only plants common in Britain before the time of Cowper's death in 1800. Beyond the flower garden is a broad vegetable plot where we can see the famous "verse manufactory" - Cowper's summer house - where many of his hymns and poems were composed. It is about the size of a railway compartment with seating room for four. The inside is covered in graffiti, the earliest dating from 1804! Beyond the fence is the "guinea orchard", so called because it backs onto the garden of the former vicarage and Cowper and Newton paid the owner a guinea a year to use it as a short cut between their homes.

John Newton's pulpit

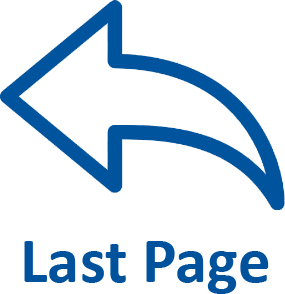

Newton's church - St Peter and St Paul - stands on the south side of the town on the banks of the River Ouse. It has a lofty spire pierced by lucarne windows, a feature more typical of Northamptonshire. Their purpose is obscure: they let in no light but doubtless provide a refuge for homeless bats or wandering pigeons. Cowper would surely have approved!

A plaque in the porch reminds us of the famous people associated with the church. In addition to Newton and Cowper, there are the Bible commentator Thomas Scott, Henry Gauntlett father of English church music, and the eccentric rector Moses Browne, for whom both Newton and Scott served as curate.

The church has two stained glass windows commemorating Newton. A modern (1973) window on the south side of the chancel shows him in the bottom panel flanked by two ships, symbolic of the two periods of his life. One is being tossed about in a storm with lightning playing about the masts, the other sailing peacefully on a flat calm sea. In the north aisle, a First World War memorial window shows Newton in the bottom left-hand corner with two slaves and a ship and Cowper is at the bottom right. Newton's pulpit has been replaced for general use, but is preserved in the south-west corner of the church.

John Newton's grave

To the right of the church door is a bay used as a children's area, and a plaque here informs us that the roof was restored by descendants of Thomas Scott (1747-1821), who succeeded Newton as curate from 1781 to 1785. He is remembered for his Bible commentary, written later in life.

In the south-east corner of the churchyard lie Newton and his wife, the beloved Mary Catlett. They were buried at St Mary Woolnoth in the City of London, where Newton completed his ministry, but reinterred here in 1893. The front of the tomb gives names and dates, but squeeze round against the churchyard wall for a more moving epitaph, composed by Newton himself:

John Newton, clerk, once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa, was by the rich mercy of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the faith he had long laboured to destroy

Churchyard and Newton's rectory

Opposite the main gate of the church is Newton's rectory, which was in use by the church until 1983. It is now a private house called The Old Rectory. Built of soft, mellow stone, it is curiously asymmetrical - perhaps extended to include an adjacent cottage. The garden backed onto that of Cowper's house separated only by an orchard. Here the two friends would meet to compose hymns for the Sunday services, later published as the Olney Hymns. Altogether 280 hymns are attributed to Newton and 62 to Cowper. The finest of these have passed into collections throughout the English-speaking world. Newton's best include Amazing Grace, Glorious Things of Thee are Spoken and How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds. Cowper contributed God Moves in a Mysterious Way, and There is a Fountain Filled with Blood.

WESTON UNDERWOOD

Cowper's Lodge

Entering the village from Olney, we pass between two massive stone pillars, as if entering someone's private estate. The place is certainly pretty enough to be just that, and Weston Underwood fully deserves its string of best-kept village awards. Here in 1786 came William Cowper with the ever-faithful Mary Unwin (John Newton had departed for a new parish in London some years before). They stayed only a dozen years but Weston Underwood has not forgotten them. The pub, called Cowper's Oak, recalls an ancient tree where Cowper used to sit, over the fields towards Yardley Chase. One story recounts that Cowper composed the lines of God moves in a mysterious way, while sheltering under its branches during a thunderstorm. The tree apparently survived until 1949 when it succumbed to a lightning strike.

Their house, now called Cowper's Lodge, faces the road not far from the pub and its superb proportions would make an estate agent struggle for superlatives. Built of soft grey stone, it has three storeys, seven white-framed windows on the first floor, with three dormers above (MK46 5JS).

The Alcove

A short drive up Wood Lane brings us to an unusual link with Cowper's time here. Standing incongruously on the edge of a field is The Alcove. With seats at the back and pillars at he front, it is part Grecian temple, part Victorian bandstand. Built by the Throckmortons - a local family - in 1753, Cowper came here on his country walks and sat down to dream and write. Indeed, he brought it into a line of his most famous poem The Task, quoted on a signboard here.

The Summit gained, behold the proud alcove that crowns it, Yes and all its prize secures.

Cowper brought the freshness of the open air to English poetry, as Constable did to painting. People come here still to admire the view and dream their own dreams. The spire of Newton's church at Olney can be seen over to the east.

The curate of Weston Underwood from 1772 was Thomas Scott, who initially held Unitarian views and confessed that he had been ordained for purely selfish motives. A lively correspondence with Newton at Olney led him to examine the Bible more closely, and he came to accept an evangelical position. Scott succeeded Newton as curate of Olney when the latter departed for a London parish in 1781. A young shoemaker living at Piddington in Northamptonshire sought out Scott for spiritual guidance, as he too struggled to find faith. His name was William Carey, later well known as a pioneer missionary to India.

Moving to London in 1785, Scott became best known for his Bible commentary published in weekly parts from 1788 to 1792. His unscrupulous publisher did well from the venture, but Scott was left exhausted and in debt. Scott's Commentary became the standard work for Bible students in Victorian times and even John Henry Newman attributed his conversion to reading Scott's work. In 1801, Scott returned to Buckinghamshire as rector of Aston Sandford.

ASTON SANDFORD

The last years of Thomas Scott "the Commentator" were spent at this rural parish, tucked away in a cul-de-sac just off the road from Thame to Princes Risborough.

The church (HP17 8JB) is tiny, with a wooden broach spire. Scott was from here from 1801 and when he died in 1821, he was buried beneath the altar table. He is commemorated by a marble tablet on the north wall, which states that by his writings he continues to proclaim the unsearchable riches of Christ. The church has framed prints of Scott and of the church in his day. It has changed little but in those days had an extra door on the south side which gave access to a marquee which could accommodate the large number of students who rode out from Oxford to hear him preach.

Scott's grandson was Sir George Gilbert Scott, the architect and leader of the Victorian Gothic revival, who built or restored countless cathedrals, churches, chapels and colleges. His grandson was Sir Giles Scott, who designed Liverpool's Anglican Cathedral.

NEWPORT PAGNELL

William Bull's house

John Bunyan was here as a teenage soldier in the Parliamentary Army under Sir Samuel Luke, governor of the town's garrison. He would have attended the church of St Peter and St Paul, although this was some time before the start of any serious spiritual quest. During his time here the incumbent vicar, Samuel Austin, was replaced by the young puritan John Gibbs, who later became Bunyan's lifelong friend.

Ejected in 1660, Gibbs began independent meetings in a barn in the High Street, where the United Reformed Church now stands. A hundred years later the minister was the William Bull (1738-1814), who lived at 73 High Street, with its white-pillared portico and archway leading to the church behind (MK16 8AB). He was a close friend and confidant of John Newton at Olney, and Newton gave such weight to his opinions that his wife was heard to make the atrocious pun "Mr Bull has become your Pope"! Bull started a small academy here to increase his income, and with his son and grandson served the church for a hundred and five years.

LUDGERSHALL

The village, just off the road between Bicester and Aylesbury, has a few old houses and plenty of grassy open space. John Wycliffe came here as vicar from 1368 to 1374, while also serving as master of Balliol College, Oxford. The east window of the Church of St Mary the Virgin (HP18 9PG), installed in 1948 in memory of a former rector, shows Wycliffe translating the Bible in one panel and the printer William Caxton in another.

JORDANS

Jordans Quaker burial ground

As befits its Quaker heritage, Jordans is a green and pleasant spot, set in peaceful countryside deep in the Chilterns. We reach it from Chalfont St Giles, turning down Twitchells Lane on the road to Seer Green. The buildings here include Old Jordans, formerly a Quaker guest house and conference centre, the Mayflower Barn and the historic Meeting House, with its pleasant orchard-like burial ground (HP9 2SN).

In the wooded graveyard, neat rows of headstones identify the early Quakers who lie here. They include William Penn (1644-1718), founder of Pennsylvania, with his two wives Gulielma Springett and Hannah Callowhill; several of Penn's children; Gulielma's mother Mary and her second husband Isaac Pennington; Thomas Ellwood, tutor to the Pennington children and friend of John Milton; and Joseph Rule, known as the White Quaker, whose simplicity of life led him to wear undyed clothing. The headstones, all uniform in height, are not original but were set in place in the mid-nineteenth century.

Mayflower Barn

The Meeting House, built in 1688, shows the symmetry and simplicity typical of Quaker buildings. The simple wooden benches face inwards and the feet of worshippers rest on a plain brick floor which is laid on bare earth. Penn, Ellwood and the Penningtons would have prayed and meditated here. The entrance lobby has the original fireplace formerly used by the resident caretaker. In 2005, there was a serious fire which destroyed much of the roof, but the building has been well restored.

Mayflower door

Beyond the burial ground is the Mayflower Barn and further up the hill is Old Jordans. Until recently these were both part of the complex of buildings with a long Quaker heritage, but are now in private ownership and not accessible to the public There is a strong tradition that the timbers in the roof of the barn were taken from the ship that carried the Pilgrim Fathers to America. The Mayflower was broken up in 1624 and there is evidence that the barn was built within a few years of that date. Research in the early twentieth century confirmed that the beams were definitely from a ship and that a central beam had cracked and been repaired - consistent with events during that historic voyage. Letters carved roughly on another beam could, it was suggested, be all that is left of "Mayflower, Harwich".

Old Jordans, originally a farmhouse, predates the other buildings by several hundred years. It was used by Quakers before the construction of the Meeting House and was certainly visited by George Fox in 1673. During its use as a conference centre, the former dining room had an old elm door reckoned to be from a ship's cabin, strengthened with oak batons and carved with a floral pattern. Could this be hawthorn or "Mayflower", and the door another link with the Pilgrim Fathers' famous vessel?

AMERSHAM

This is a town of independent spirit and its zeal in matters of religion earned it terrible retribution in centuries past. It is in two parts - the Old Town lies along the river Misborne, with a broad main street, a market hall built in 1682, ancient inns, almshouses and wisteria-covered cottages. Replace the cars with carriages and it could be the set for another Jane Austen TV series. Amersham-on-the-Hill is mostly modern and grew up around the railway station half a mile away.

Amersham Old Town

Amersham became a centre of the Lollard movement - followers of John Wycliffe and heralds of the Reformation. In 1414, four Amersham men were among a group of Lollards burned in London. The persecution continued intermittently for the next century and came to a head in 1506 with the burning of William Tylsworth on the hill above the town. It is interesting to recall that this was a decade before the proclamation of Luther's ninety-five theses and three years before the birth of John Calvin. Amersham men were suffering as Protestants before Protestantism had been properly defined.

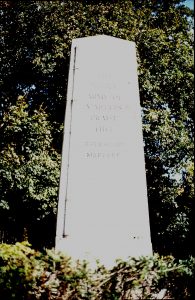

Martyrs memorial

The Martyrs Memorial (HP7 0DB)is a ten-minute walk from the centre of the Old Town: down Church Street, behind St Mary's church, along the river and round the edge of a sloping cornfield. The memorial, a stone cenotaph about twelve feet high was erected in 1931 and carries the inscription The noble army of martyrs praise thee. It names Tylsworth and six others, including a woman, who suffered death at the stake here between 1506 and 1521. Also mentioned is Thomas Harding, who died at Chesham nearby, and is reckoned to be the last Lollard martyr. At Chesham, there are memorials to Harding in St Mary's churchyard (HP5 1HY) and on White Hill (HP5 1AB).

150 years later, Amersham folk were still suffering for their beliefs, but this time it was the teachings of George Fox rather than Wycliffe that got them into trouble. Mary and Isaac Pennington, mother and stepfather of William Penn's wife Gulielma Springett, were prominent Quakers. They had suffered the confiscation of their home at Chalfont Grange and for a time resided at Bury Farm in the Old Town (HP7 0HE). It stands on the corner of London Road and Gore Hill, immediately opposite Tesco supermarket. It was here that Penn came to court the beautiful Guli. The Meeting House beneath a spreading chestnut tree in Whielden Road was built in 1685 and would have been known to Penn. Later, the Penningtons moved to Woodside Farm at Amersham-on-the-Hill. It stood on the site of the present Community Centre in Chiltern Avenue. Most of this consists of modern sports and leisure facilities, but facing the road are older barn-like buildings which could have been part of the original farm.

Another prominent Quaker with links to the area was Thomas Ellwood (1639-1713), who was employed as tutor to the Penningtons' younger children. It was Ellwood who in 1665 snatched John Milton and his family from plague-ridden London and brought them to Chalfont St Giles for safety. Ellwood later lived at Ongar Hill Farm, just off the road between Amersham and Beaconsfield, where he died in 1713.

CHALFONT ST GILES

John Milton's cottage

From the main Amersham road we turn down the quaintly named Pheasant Hill and pass through the old part of the village. On the left is Milton's Cottage, now a museum (HP8 4JH), still surrounded by fields and much as it was in the seventeenth century. This was the "pretty box" secured by his friend Thomas Ellwood, to enable John Milton (1608-1674) to escape the London plague.

It seems remarkably small for a man of Milton's standing, but in the circumstances he was probably glad to accept. The great poet was by this time totally blind and, as an apologist for Cromwell's regime, was noticeably out of favour with the restored monarchy. It was time to keep a low profile, and it was in these modest surroundings therefore that Paradise Lost was completed and, at the suggestion of Ellwood, Paradise Regained begun.

The ground floor consists of three rooms arranged in an approximate L-shape. The first has prints of Milton acting as Cromwell's secretary and attending the Westminster Assembly of Divines, and a cabinet with foreign translations of Milton's works. The second room with its splendid open fireplace contains items of local interest, including early paintings of the cottage showing that the present structure is largely unchanged. It was in the back room that Milton did most of his writing, dictating to his daughters or sympathetic friends. Here we find the things most directly concerned with his life and work. There are three portraits, including a posthumous original by Godfrey Kneller. A cabinet contains first editions of his works and even a lock of his hair, which moved John Keats to pen a verse quoted here.

The cottage garden, listed by English Heritage in its own right, is beautifully laid out and planted with flowers and herbs mentioned in Milton's poetry.

STOKENCHURCH

Stokenchurch is a pleasant place, although the M40 rumbles past less than half a mile away. The village has acres of green space but few interesting or attractive buildings.

We come here in search of Hannah Ball (1734-1792), who could justly claim to be the founder of Sunday Schools. Her work with children began in 1769, predating that of the better known Robert Raikes by some eleven years. One of a family of twelve herself, she prepared for her calling by looking after the children of a cousin and later those of her widowed brother.

Her grave is in the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul (HP14 3TH), itself an ugly pebble-dashed building. On the east side of the churchyard is a row of lichen-covered tombstones where the names of Hannah Ball and other family members can just be made out. There appears to be no trace of her school building or the chapel she had built from plans provided by John Wesley, with whom she had a lively correspondence.