City of London

HMS Belfast & the Tower of London

The capital of Great Britain is not a single city but a collection of cities, towns, boroughs and villages which have merged together to form a vast metropolis of some 8,000,000 souls. The City of London itself, which has given its name to the whole, occupies slightly more than the traditional "one square mile" on the north side of the Thames and is famous as the financial centre of Britain. The present boundary covers an area about twice that enclosed by the ancient city walls, remnants of which can still be seen in places.

Within the City, ancient buildings like the Tower of London rub shoulders with modern office blocks, whose unusual shapes seem to defy architectural convention, and even gravity itself, and have earned a variety of nicknames like the Gherkin, the Cheesegrater and the Walkie Talkie.

City offices

The city once had 112 churches to serve its teeming population. Today there are thirty-nine, and a further ten with towers only remaining. The City's two major conflagrations were the Great Fire of 1666 and the London Blitz of 1940-41. Thirty-five churches lost in the Great Fire were never rebuilt. Over fifty were reconstructed to the designs of Christopher Wren, of which twenty-one have since been lost, mainly to nineteenth century commercial expansion. At least five churches disappeared for ever in the Blitz, with many others being severely damaged. Nevertheless, there is still a wealth of history and architecture to be found within the survivors. As the population of London moved towards the suburbs - a process which has been going on for nearly two hundred years - so the ministers of City churches had to find wider roles for their parishes. The Samaritans, the Church Army and the Church Missionary Society all began in City churches. We tell their stories below.

ST PAUL'S CATHEDRAL

St Paul's Cathedral

There has been a church dedicated to St Paul at the top of Ludgate Hill since Mellitus was appointed bishop by Augustine in 604. The present cathedral, the fifth to occupy the site, is the masterpiece of Christopher Wren, on which he worked for fifty years. It replaced the famous Old St Paul's, which was already in a poor state of repair when it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

As we proceed through the magnificent baroque interior, it is soon apparent that St Paul's seems more interested in commemorating heroes of the battlefield than champions of the faith. Generals and admirals of the Napoleonic wars, heroes of the Indian Mutiny and commanders of the Second World War all have their tombs, statues or marble plaques. Memorials to veterans of spiritual battles seem few and far between, but there are some. One who had a foot in both camps, so to speak, was General Charles Gordon, whose effigy is in the north aisle. Slain at Khartoum in 1885, military genius and sincere Christian conviction formed a strange blend in this unusual Victorian personality.

In the north transept is a chapel for private prayer where Holman Hunt's painting The Light of the World is displayed. The picture illustrates the text in Revelation Behold I stand at the door and knock. In the style of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, some find it inspirational, but for others it is ghostly and unreal.

Near the entrance to the crypt is a statue of the prison reformer John Howard (1726-1790) by John Bacon. Reflecting the eighteenth century vogue for all things classical, he is shown in a Roman toga. Howard was a country gentleman who, almost by accident, became a great social reformer. In middle age, he began an untiring crusade to improve prison conditions in every part of Europe, which was only cut short when he died of smallpox at Cherson in the Ukraine. We meet him again at Cardington in Bedfordshire.

Wren's model of St Paul's

The Crypt contains the tombs of many of the nation's greatest heroes including Nelson and Wellington. Here too lies Wren himself, with his famous epitaph Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice (Reader if you require a monument, look around you). The east end forms a chapel dedicated to the Order of the British Empire, founded by King George V in 1917. Among those commemorated here are two notable figures in the early missionary movement, Reginald Heber (1783-1826) and Henry Venn (1796-1873). Heber was appointed Bishop of Calcutta at the early age of thirty, but succumbed to cholera only three years later. He left us with some famous hymns including Holy, holy, holy. He has a statue in one of the recesses here. On a pillar close by, is a marble tablet to Venn who was a prebendary of St Paul's. Son of John Venn, a leader of the Clapham Sect, he acted as honorary secretary of the Church Missionary Society for thirty critical years. He personally examined nearly five hundred clergy who were sent abroad on missionary service.

St Paul's dome and cross

Towards the western end of the crypt lie two men of restless energy who faced the challenge of evangelising the industrial cities of Victorian Britain by founding organizations designed for the task. A quotation from the will of Sir George Williams (1821-1905) provides his epitaph: My last legacy, and it is a precious one, is the Young Men's Christian Association. I leave it to you, beloved young men of many countries, to carry on and to extend. A brass plate on the floor marks his tomb.

Immediately opposite is a tablet to Wilson Carlile (1847-1942), prebendary of St Paul's and founder of the Church Army, the established church's response to William Booth's energetic Salvation Army. His epitaph reads A man greatly beloved, who loved and served all, especially those thought most unlovable. Another tablet commemorates Sir William Smith (1854-1914), founder of the Boys Brigade.

Back at ground level there is a list of all the Bishops of London by the entrance to the Gallery in the south aisle. Several of them went on to become Archbishops of Canterbury, and a few met gruesome or untimely ends, but not many names would be recognized by the average layman today. However, we will meet Mellitus (bishop in 604), Dunstan (959) and Nicholas Ridley (1550) at other places.

ST PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

John Wesley

To the north and east of the cathedral is the green open space of St Paul's Churchyard, which in past centuries served as a forum for heated debate on all matters of church doctrine and practice. Today it provides city workers with a shady spot to eat their sandwiches. A circular cobbled area has a memorial to the people of London who endured the Blitz, and here too is a statue of John Wesley priest, poet and teacher of the faith, who has many links in the City.

St Paul statue

The column with a gilded statue of St Paul marks the site of St Paul's Cross, an open-air pulpit which stood here from the twelfth century until it was pulled down in 1643. It served as an ecclesiastical version of Speakers' Corner, where bishops harangued royalty, papal bulls were promulgated and proclamations made. At the time of the Reformation it served as a major platform for the new teaching. The present column was erected in 1910 to commemorate the former Cross whereat, amid such scenes of good and evil as make up human affairs, the conscience of church and nation through five centuries found public utterance.

ST ANDREW-BY-THE-WARDROBE

St Andrews by the Wardrobe

The church stands on Queen Victoria Street in Blackfriars, opposite an ugly concrete block called Baynard House. It was destroyed in 1666, rebuilt by Wren and gutted again in 1940. It has been restored with plenty of light new woodwork.

From 1766 to 1795 was the rector was William Romaine (1714-1795), a lesser known figure in the evangelical revival. Romaine was a lecturer at St Dunstan's-in-the-West from 1749 and also held lectureships at several other London churches. Until the arrival of John Newton at St Mary Woolnoth in 1779, Romaine was the only incumbent of a London church with evangelical views. Using the analogy of a Christian army, one author compared Romaine to the artillery - lobbing shells and mortars of sound doctrine at a hostile city and complacent church, while Wesley and Whitefield formed the cavalry, continually on the move. Romaine's works were published as The Life, Walk and Triumph of Faith between 1763 and 1795.

From 1799 to 1812, committee meetings of the newly founded Church Missionary Society were held in the church. For many years the offices of the British and Foreign Bible Society were located next door at 146 Queen Victoria Street, which has the text The word of the Lord endureth for ever above the door.

ST DUNSTAN-IN-THE-WEST

St Dunstan-in-the-West

On the north side of Fleet Street looking down towards St Paul's, this impressive church was built between 1831 and 1833, replacing an earlier church on the site. The main body of the building is octagonal, while the stone tower beside the pavement has an overhanging clock with wooden figures striking the bells, which were taken from the original church.

The former building provided a pulpit for many prominent preachers over several centuries and the doctrines of the Reformation, the puritans and the evangelical revival were all heard here. William Tyndale (1494-1535) preached at St Dunstan's during his brief residence in London in 1523-24. He arrived from rural Gloucestershire to seek the support of Bishop Tunstall in translating the Bible. Unsuccessful, he fled for ever to the continent to carry on his great work there. In the 1660s, the well-known puritan pastor Richard Baxter (1615-1691) preached here.

In 1749 William Romaine (1714-1795) was appointed lecturer and held this office for forty-six years, despite determined opposition from other church officers. Sometimes the vicar would occupy the pulpit and for many years Romaine gave evening lectures by the light of one candle as the churchwardens refused to heat or light the church.

From 1820 to 1824, the curate here was Henry Venn (1796-1873), the son and grandson of prominent evangelicals, who later spent thirty-two years as secretary of the Church Missionary Society.

ST SEPULCHRE-WITHOUT-NEWGATE

St Sepulchre without Newgate

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre (known as St Sepulchre's) stands on Newgate Street, across from the Old Bailey, once the site of Newgate Prison. It is the largest church in the City, with a pinnacled white stone tower. The notice board reminds us of famous people formerly associated with the church. Chief among these was a former vicar, John Rogers, who had the unhappy distinction of being the first protestant martyr of Queen Mary's reign, burned at the stake at Smithfield on 4th February 1555. Many more were to follow. One of his parishioners was John Daye, a printer who shared Rogers' views and also his prison cell. Daye, however, survived Mary's purges and went on to print that celebrated record of those times, the Acts and Monuments of John Foxe, better known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

Newgate Prison itself was the scene of John Wesley's efforts to bring spiritual solace to condemned men and, later, Elizabeth Fry's attempts to reform the conditions of female prisoners. At one point Wesley found himself excluded by the prison authorities and also banned from Bethlehem Hospital, the mental asylum known as Bedlam. He made the wry comment in his diary So now we are forbid to go to Newgate for fear of making them wicked; and to Bedlam for fear of driving them mad! Among those who found themselves on the wrong side of Newgate's prison bars were William Penn, the Quaker, and several of the martyrs of Queen Mary's reign, not least John Rogers himself. A Nottinghamshire man, Thomas Helwys, regarded as one of the founders of the Baptist Church died in Newgate prison in about 1616.

Somewhere within the Old Bailey is a memorial referring to Penn and his fellow Quaker William Mead. It is not to the men themselves but to the jury who in 1670 refused to convict them for "unlawfully preaching in the street". The judge ordered them to reconsider their verdict, but they declined to change it. Furious, he locked them up for two days without food or water but they refused to be swayed. They thus established not only the independence of juries, but also provided a template for freedom of speech and worship in England

Running down to Farringdon Street from St Sepulchre's is Snow Hill. It was in a house here, now gone, that John Bunyan died in 1688. He had ridden back from Reading in appalling weather and took shelter with his friend John Strudwick, a grocer. He developed a severe chill and, despite signs of recovery, pneumonia set in and he died a few days later. He is buried in Bunhill Fields.

SMITHFIELD

St Bartholemew gateway

West Smithfield forms a large roundabout linking Farringdon Street, Long Lane, Giltspur Street and the pedestrianised section of Little Britain. On one side is the brightly painted Smithfield meat market and on the other St Bartholemew's Hospital. Tucked away through a medieval gateway is the church of St Bartholemew-the-Great, founded in 1123 by Rahere, a courtier of Henry I, son of William the Conqueror. The church and gateway escaped the Great Fire of 1666, which engulfed so much of the city and are among the most ancient buildings in London.

Protestant martyrs memorial

For Protestants, Smithfield has only tragic memories. Being just outside the old city walls, it was considered a suitable place of execution. In particular, it was the place where more than sixty were burned at the stake for their faith, mainly during the reign of Queen Mary. Their names are all recorded on a panel at St James Church, Clerkenwell. On the wall of the hospital is a granite memorial erected in 1870. Surmounted by the text Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord, it records that Within a few feet of this spot John Rogers, John Bradford, John Philpot and other servants of God suffered death by fire for the faith of Christ, in the years 1555, 1556, 1557.

The Protestants have to share wall space with memorials to other martyrs who suffered here in a variety of causes. These include Scottish patriot William Wallace, and Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants Revolt of 1381.

ST JAMES,CLERKENWELL

Smithfield Martyrs

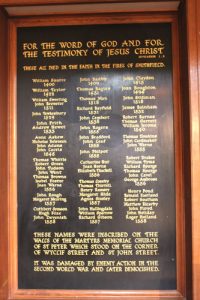

Just off the busy Clerkenwell Road is the relatively peaceful Clerkenwell Green, with quaint pubs and eighteenth century houses. Rising over the scene is the handsome Georgian church of St James, with its white stone spire and large planes trees in the churchyard. One of the window spaces on the south wall is taken up with a large panel commemorating the Protestants who were martyred at Smithfield. Inscribed in gold are the names of sixty-six men and women, beginning with William Sautre, a follower of Wycliffe, who died in 1400. It ends with a group who were burned at the stake in 1558, during the final months of Queen Mary's reign. Her death and the accession of Good Queen Bess brought a merciful cessation. Among the most famous names are John Frith, who helped William Tyndale with his New Testament translation; Anne Askew, a friend of Henry VIII's third wife, Jane Seymour; John Rogers, vicar of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate; John Bradford, chaplain to Bishop Nicholas Ridley and John Philpot, Archdeacon of Winchester. The names were formerly inscribed on the walls of the Martyrs Memorial Church which stood on the corner of Wyclif Street and St John Street, but were transferred here when that church was destroyed in World War II.

CHARTERHOUSE

Charterhouse entrance

Charterhouse Square is a large open space off Aldersgate Street, mostly surrounded by modern flats and offices. On the north side are some older buildings including an ancient archway giving access to the Charterhouse site. Following the closure of the Carthusian monastery in 1533, the Charterhouse became a boys' school, which removed to Godalming, Surrey, in the nineteenth century. John Wesley came here as a pupil in about 1714. The site is not generally open to the public, but afternoon conducted tours take place during the summer.

ALDERSGATE STREET

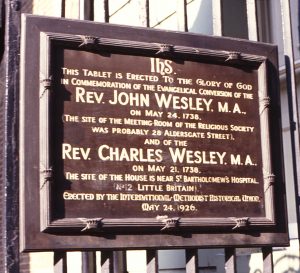

Wesley plaque

A plaque on the railings of St Botolph's Church, commemorates the "evangelical conversion" of John Wesley on May 24th 1738, and that of his brother Charles three days earlier. John Wesley's account of the occasion is well known. In the evening I went very unwillingly to a society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change God works in the heart through faith, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.

The house has long since disappeared and its exact location is unimportant. The churchyard plaque suggests 28 Aldersgate Street, while a sign outside the Museum of London mentions Old Nettleton Court. Both would now be submerged under the redeveloped Barbican site. Charles Wesley's conversion took place at the house of John Bray, the site of which is marked by a plaque on the wall of 5 Little Britain nearby. On the night of his conversion John Wesley was carried triumphantly to this house by his friends and it became the London home of the brothers until the acquisition of the Foundry Chapel.

At the south-west corner of the Barbican, steps lead up to the Highwalk, with its shops and restaurants above street level. This is also the entrance to the Museum of London, where there is a memorial to Wesley and a facsimile of his famous diary entry in bronze.

St Botolph's church now serves as the base for Christian Heritage London, from where guided walks are arranged to places of interest in the area (see www.christianheritagelondon.org)

BREAD STREET and ST MARY-LE-BOW

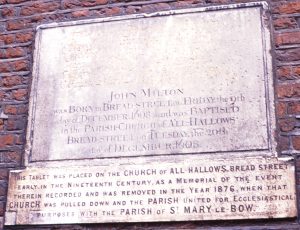

John Milton memorial

Although barely two hundred yards long, Bread Street had two churches when the poet John Milton was born here in 1608. All Hallows and St Mildred's were both destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and both rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren. All Hallows was pulled down in 1876 and St Mildred's was destroyed, along with the rest of Bread Street, in the London Blitz of 1940. Milton was baptized at All Hallows on 20th December 1608. Early in the nineteenth century a tablet was placed there to commemorate the event, but when All Hallows was demolished, it was moved to St Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside nearby. It can be seen on the outside wall in St Mary's churchyard, together with a poem in praise of Milton. St Mary's itself suffered severely in World War II. Wren's tower and steeple survived but the rest of the church had to be rebuilt and the famous Bow Bells were silenced until 1961.

In the early eighteenth century, the vestry of St Mary's, recently rebuilt by Wren, was used for the founding of two Anglican missionary societies - the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

ST GILES, CRIPPLEGATE

St Giles Cripplegate

In a place where everything seems aggressively new, St Giles church and a ruined bastion of the medieval city wall are the sole remnants of old London. At the heart of the Barbican complex in Aldersgate, it floats like a ship becalmed on a sea of modern red brick, with blocks of flats and glassy offices rising like icebergs all around. In summer, luxuriant growth from window boxes hangs down from the flats.

The stone tower with its red brick top and wooden turret can be seen from many directions, but to get there, use the stairs from a section called The Postern on the raised Highwalk or approach at ground level from Wood Street. St Giles survived the Great Fire of 1666, but was heavily restored in Victorian times, lost its roof and most of its interior furnishings in the Blitz and had to be rebuilt after the War.

This is the church where the poet John Milton and the martyrologist John Foxe were buried, the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell was married, the puritan Thomas Manton preached and John Wesley's grandfather Samuel Annesley was rector.

John Foxe may have preached in St Giles in the 1570s and was buried here in 1587 but the site is not marked. A stone at the threshold of the chancel marks the presumed site of John Milton's grave in 1674, but it may be that of the poet's father and namesake. It has long been suggested that the bones of Milton himself were turned up in 1790 and sold as souvenirs! Clearly proud of its connection with Milton, who lived in what is now Beech Street, the church has a bronze statue of him in the south aisle and two busts, one set into the south wall.

Flanking the main west door are four busts, donated by the Victorian philanthropist J. Passmore Edwards, of John Bunyan, Oliver Cromwell, the novelist Daniel Defoe and, of course, Milton. Cromwell came here in August 1620 to marry Elizabeth Bourchier, which proved a happy and fruitful union despite the turmoil of the times.

A brass plate in the vestibule lists the rectors since 1135. They include Lancelot Andrewes, one of the leading compilers of the King James Bible and Samuel Annesley rector from 1658 to 1662. It was his daughter, the spirited Susannah, who married Samuel Wesley and became the mother of John and Charles, not to mention seventeen other children! Annesley lost his living in the Great Ejection of 1662, along with some 2,000 others who refused to conform to the Prayer Book rules laid down by the Act of Uniformity.

WESLEY'S CHAPEL

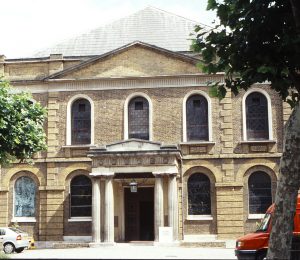

Wesley's Chapel

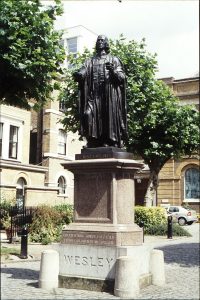

For nearly forty years John Wesley's London base was a converted cannon foundry near Moorfields, which had been severely damaged by an explosion in 1716. There are frequent references to "The Foundery" in his diary. In 1778, a new chapel was opened in City Road, and Wesley's Chapel stands today as the mother church of world Methodism, with a statue of the founder in the cobbled forecourt and the inscription The world is my parish. Nothing remains of the original foundry building.

Wesley's House, in which he lived for the last eleven years of his life, is beside the chapel. He died here in 1791 and is buried with many early Methodist leaders behind the chapel in the small, peaceful graveyard. In 1984, an excellent Museum of Methodism was opened in the chapel basement.

John Wesley statue

Set back from the busy traffic in City Road, the chapel is built of plain yellow brick, with arched windows and a classical porch supported by fluted columns. Inside, the first impression is one of symmetry, elegance and simplicity. Wesley himself described it as perfectly neat, but not fine. The ceiling, with gilded plasterwork in the style of Robert Adam, supports a large central chandelier with four smaller ones at the corners. The gallery, covering three sides, was originally supported by pillars made from ships masts donated by George III. These were replaced in 1891 by columns of French jasper, the gift of Methodist churches from around the world. Some of the original pillars are preserved in the entrance lobby. The motifs around the gallery show a dove and serpent, chosen by Wesley to illustrate the command of Jesus to be wise as serpents, gentle as doves.

The pulpit was originally in three tiers, following the Methodist practice of having a preacher, reader and precentor leading various parts of the service. The present pulpit is the top tier of the original and is supported on an arch so that the altar beyond is still visible to those sitting in the pews. The apse behind the pulpit has wooden panels inscribed with the commandments and creed, headed by the words HOLY, HOLY, HOLY.

John Wesley's tomb

The organ and stained glass windows have been added since Wesley's day. The ground floor has biblical scenes, but those in the gallery show events from the early history of Methodism - Wesley's conversion in Aldersgate Street, Charles Wesley preaching to native Americans in Georgia and John preaching in the open air. One window showing the mantle of Elijah falling on Elisha is in memory of Francis Asbury, whom Wesley commissioned as the leader of Methodism in America in 1771. There are memorial tablets to leading Methodists around the walls. Those to John and Charles Wesley and Thomas Coke are behind the pulpit.

A smaller chapel on the south side of the main building, known as the Foundry Chapel, contains original pews from the foundry and also its pewter collection, plates and lectern. There is also a small organ used by Charles Wesley.

In the graveyard behind the chapel, overlooked by shiny new offices, is John Wesley's tomb, with a simple stone monument topped by an urn. The epitaph, by Adam Clarke, is rather more effusive than one composed by Wesley himself during a serious illness in 1753, in which he stated that he left less than ten pounds after his debts are paid. It is reckoned that the mortal remains of some 5,000 early Methodists are interred here, but one who declined that honour was Charles Wesley. True Anglican to the last, he was laid in the consecrated ground of his parish church at Marylebone.

MUSEUM OF METHODISM

Located in the basement of the chapel, this excellent display is well worth a visit, which should not be rushed. It covers the entire history of the movement from the earliest days to the present. Exhibits cover the state of England before the evangelical revival, the Wesley family in Epworth, the "Holy Club" at Oxford, Wesley's failure in America, his conversion and adoption of open-air preaching and the subsequent growth of Methodism. Contemporary commemorative china and porcelain and other Wesleyana are also on display.

The Museum has some original paintings, including the famous deathbed scene, with Wesley uttering the well-known lines The best of all is, God is with us. Artistic licence has allowed rather too many people around the bed, as will be seen from the size of the room in his house next to the chapel.

WESLEY'S HOUSE

John Wesley's house

Officially 47 City Road, Wesley's House was built in 1779 and is arranged on five floors, including a basement. This might seem generous for a bachelor existence, but each floor contains only two rooms of modest size, with an extra small extension at the back, when an annexe was added later.

It is preserved as a museum, with many of Wesley's personal possessions, including his clothes, books, furniture and shoes (remarkably small). There is also a device Wesley used for electric shock treatment of those suffering from nervous complaints, for which he claimed remarkable success. He had followed the researches of Benjamin Franklin and speculated prophetically on the future importance of electricity. There are several portraits of Wesley and also of his brother Charles and John Fletcher. Fletcher predeceased Wesley, but would otherwise have succeeded him as the leader of Methodism.

Wesley's bedroom, where he died on 2nd March 1791, is on the first floor. Rising at 4.00 am, he would spend time in prayer in the little adjoining study, sometimes described as the Powerhouse of Methodism. The top two floors provided accommodation for visiting preachers. On one occasion, finding that they had all overslept and failed to conduct an early morning service, Wesley insisted that those in his household, like himself, should be in bed by 9.00 pm.

BUNHILL FIELDS

Bunyan's grave

Immediately opposite Wesley's Chapel is the non-conformist burial ground, in use for about 200 years before its closure in 1854. Denied burial in the consecrated ground of their parish churches, London's Baptists, Presbyterians, Independents and Quakers were interred at Bunhill Fields and we can find the graves not only of many spiritual giants, but also those famous in other spheres including the writers Daniel Defoe and William Blake.

Severely damaged by bombs in World War II, the burial ground has been restored as a leafy park where City workers can eat their sandwiches or watch the squirrels. It also provides a convenient footpath between City Road and Bunhill Row. The headstones are mainly behind railings to prevent vandalism but the ground staff will usually allow access on request.

Isaac Watts tomb

A display board gives the location of the most famous occupants. John Bunyan's tomb, restored by public subscription in 1862, is in the paved area at the centre, with scenes from Pilgrim's Progress on the sides. He died in Holborn in 1688. Hymn writer Isaac Watts lies under a tree to the right of the path from City Road. The tomb of puritan scholar John Owen, damaged at one corner, is on the opposite side not far from Bunyan.

Surprisingly perhaps, Susannah Wesley, mother of John and Charles, is also interred here, alongside a footpath on the south side. As the wife of one Anglican minister and mother of two others, burial in her parish churchyard would have seemed more appropriate. She died in 1742, well before "Methodism" was recognized as another branch of non-conformity. Her headstone of white marble stands out prominently and carries the lines

In sure and certain hope to rise And claim her mansion in the skies A Christian here her flesh laid down The cross exchanging for a crown

Visitors with a knowledge of church history can interest themselves by searching for familiar names. Near the Bunhill Row entrance is the tomb of David Nasmith (1799-1839), founder of City Missions and not far away a granite obelisk to hymn-writer Joseph Hart (1712-1768). Nor should we forget the lady whose virtues were extolled by her husband, who inscribed on her tombstone that in her final illness she was relieved of 240 gallons of water over a period of sixty-seven months, without complaint!

George Fox memorial

The Quaker section of Bunhill Fields is detached from the main part. We reach it from Banner Street across Bunhill Row. Under an archway formed by new flats is an open space with a children's playground and Quaker centre. A stone set into the grass beneath an enormous plane tree reminds us that this is the burial place of many Quakers including their founder George Fox (1624-1691). There are no individual headstones - perhaps destroyed by wartime bombing. Although not mentioned by name, Fox's chief lieutenant George Whitehead (1636-1723), who pleaded for freedom of conscience with six English monarchs, lies here too.

SPITAL YARD

Samuel Annesley's house,

Close to Liverpool Street Station and dwarfed by the towering glass offices of City banks is an extraordinary survivor. At the end of Spital Yard, a cul-de-sac off Bishopsgate, is the seventeenth century home of the Rev Samuel Annesley (1620-1696) and it was here that his daughter Susannah was born on January 20th 1669. In due course, she married the Rev Samuel Wesley and became the mother of John, Charles and many other children. The three-storey house has recently been restored.

Annesley, at one time a ship's chaplain in Cromwell's navy, was appointed vicar of St Giles Cripplegate in 1658, but was ejected following the Act of Uniformity in 1662. Thereafter he preached privately wherever the opportunity arose.

ST STEPHEN'S, WALBROOK

St Stephen's Walbrook

At the top of Walbrook is St Stephen's - square, domed and with perfect symmetry. The dark wooden panelling and plain white columns emphasize its excellent proportions. It was built by Wren to replace a larger Gothic church destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. The seats are arranged in a circle around a marble altar table sculpted by Henry Moore. From 1652 to 1662 the rector of the former church was Thomas Watson, a puritan who combined a deep knowledge of the Bible with sound common sense and is remembered for his work A Body of Divinity, a collection of sermons based on the Westminster Catechism.

With congregations departing to the suburbs, many City churches in post-war years were searching for a role. St Stephens found its vocation in the work of a former rector, the Rev Chad Varah, who in 1953 founded the Samaritans, the telephone helpline for those tempted to suicide. For many years the organisation had its headquarters in the crypt, for which a new entrance was added on the north side. The worldwide version of the Samaritans, known as Befrienders International, was also founded here in 1974.

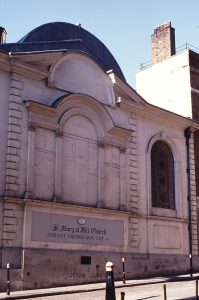

ST MARY WOOLNOTH

St Mary Woolnoth gateway

In the English baroque style of Nicholas Hawksmoor, St Mary Woolnoth straddles the divide between Lombard Street and King William Street. For twenty-eight years it was the pulpit of former slave trader John Newton (1725-1807), and there can be few more ornate pulpits in London. Newton was for sixteen years curate of Olney in Buckinghamshire, where most of his greatest hymns were written in collaboration with his friend William Cowper, but came here as vicar in 1779 and remained for the rest of his life.

John Newton memorial

On the north wall a marble tablet carries Newton's self-composed epitaph ....once an infidel, a libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa, was by the rich mercy of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the faith he had long laboured to destroy. Newton was buried in the vault beneath the church, but later in the nineteenth century his remains were transferred to the churchyard at Olney, where the epitaph is repeated on his tomb.

On his arrival in London from a rural parish, Newton attracted more influential congregations and his preaching had a profound effect on many, including the young William Wilberforce, social reformer Hannah More and Charles Simeon, who preached for fifty years in Cambridge. Particularly significant was his influence on the growing movement for the abolition of the slave trade. Those gathering around Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson found in Newton not only a wholehearted supporter, but also one with long personal experience of its evils.

ST MILDRED'S COURT

This is a little courtyard off Poultry, close to the junction with Prince's Street. A blue plaque records that from 1800 to 1809 the home of the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry (1780-1845) stood on the site.

ST ANDREW UNDERSHAFT

The church is one of the City's survivors, having miraculously escaped the Great Fire, Hitler's bombs and nineteenth century developers. It is approached from St Mary Axe, with most of the nave tucked in behind offices in Leadenhall Street. It is used as a church conference centre and is not generally open to the public.

On the north wall is a brass plaque to William Walsham How (1823-97), who was rector from 1879 to 1888. He also served as Suffragan Bishop of East London and led many missions in the area. He is remembered particularly for his love of children, and for his output of hymns, which include O Word of God Incarnate and For all the Saints who from their Labours Rest, from which a line is quoted on the plaque. He made strenuous efforts to interest students from public schools and universities in the needs of the East End.

ST BOTOLPH WITHOUT ALDGATE

St Botolph, Aldgate

St Botolph (not to be confused with its namesake in Aldersgate) is set on a traffic island formed by Aldgate High Street and St Botolph's Street, on one of the busy eastern approaches to the City. From 1708 to 1722 the vicar was Thomas Bray (1658-1730), who is remembered as the founder of two Anglican missionary societies, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. Both date from the early part of the seventeenth century and both are still active in revised form today. Bray was involved in setting up church structures and providing lending libraries for clergy in the American colony of Maryland, which he visited in 1699.

The present dark brick building dates from 1741 and was designed by George Dance the Elder. The church today ministers to the needs of the poor and homeless from a kitchen in the crypt. In a glass-doored chapel to the left of the altar is a memorial to Bray, placed here in 1980 to mark the 250th anniversary of his death.

ST MAGNUS THE MARTYR

St Magnus the Martyr

The churchyard on busy Lower Thames Street used to be the approach to Old London Bridge, which, with its shops and buildings, was for centuries the only crossing of the Thames in London. There is a model of the bridge in the foyer of the church.

In 1564, towards the end of a long and useful life, Miles Coverdale (1488-1568) became rector here. When he died four years later, he was buried at St Bartholemew Exchange, but when that church was pulled down in the nineteenth century, his remains were transferred here. There is a memorial tablet praising his achievements on the east wall, to the right of the altar.

As a young man, Coverdale entered the monastery of the Austin Friars but adopted Protestant views and left. He was the friend of many powerful figures including Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell. In 1529 he collaborated with William Tyndale at Hamburg and published the first complete English translation of the Bible, dedicated to Henry VIII, in 1535. In 1538, at the invitation of Cromwell, he supervised the publication of the Great Bible at Paris. On the accession of Edward VI, he was appointed chaplain to the young king and also Bishop of Exeter. When Edward was succeeded by his Catholic half-sister Mary, Coverdale was expelled from his bishopric, but avoided the fires of Smithfield by going into exile in Denmark and Germany.

ST MARY-AT-HILL

St Mary at Hill

The church of St Mary at Hill backs on to the street of that name, presenting a doorless facade with an impressive overhanging clock. The entrance is through an iron gate to the right via the small churchyard. The list of rectors by the door starts with Thomas a Becket, but the name we are interested in is Wilson Carlile, who came here in 1891 and remained for thirty-five years. Carlile had founded the Anglican Church Army in 1882, clearly impressed by the work of William Booth, founder of the non-conformist Salvation Army. When he arrived, most of the congregation had long departed for the suburbs, but he filled the church to capacity for three decades and directed the growing operations of the Church Army in relief and ministry to the poor.

The church was rebuilt by Wren after the Great Fire and survived the Blitz with, to quote John Betjeman, the most gorgeous interior in the City. Alas, this was largely destroyed by a disastrous fire in 1988. The organ and wooden furnishings at the west end were less severely affected and have been restored, but the altar-piece, pulpit and pews have all gone. Apart from his name on the list of rectors, there appears to be no other memorial to Carlile.

ALL HALLOWS BY THE TOWER

All Hallows by the Tower

As the guide book tells you proudly, the church has walls 400 years older than the Tower of London itself and stands on a Roman villa 400 years older than that. In the crypt there are tiles that have been here for 1800 years. The church survived the Great Fire by the simple expedient of blowing up the surrounding houses, as described by that famous eye-witness Samuel Pepys. This was carried out on the orders of Sir William Penn, head of the Navy Office and father of the founder of Pennsylvania.

William Penn plaque

Penn's son William Penn was baptised here on 23rd October 1644, an event commemorated by a blue plaque on the outside of the church. The baptismal register of the time is kept in the church but the original font was removed to Christ Church, Philadelphia, in Penn's own lifetime. Penn angered his father, a distinguished admiral, by adopting Quaker views, but his position in society enabled him to offer some protection to the Society of Friends, who were suffering severe persecution. A gift of land in America from Charles II, in lieu of debts owed to his father, led to the founding of the Quaker state. Another American connection is the marriage of John Quincy Adams, sixth president of the United States, which took place here in 1797.

In London's other great ordeal, the blitz of 1940, All Hallows was reduced to a shell but has now been well restored. From 1922 to 1963, the vicar was the Rev "Tubby" Clayton, the founder of Toc H, a welfare group for ex-servicemen, and the church is regarded as the spiritual home of the movement.